“The secret word is anniversary…”

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on Oct 27th 2012

On this date in 1947, the program that finally found a way to make good use of the one-of-a-kind comic talent of Julius “Groucho” Marx premiered: You Bet Your Life. A “quiz show” that really served as mere window dressing for Groucho’s rapier wit, its debut over ABC Radio was originally met with a bit of trepidation by the press—Newsweek observed that featuring Groucho as a quizmaster was the equivalent of “selling Citation to a glue factory.” But it didn’t take long before the fourth estate agreed that You Bet Your Life was the perfect vehicle for the comedian’s talents—it would spend roughly the next fifteen years as a radio and TV staple, even winning a Peabody Award in 1949.

Groucho had been looking for success in radio as far back as 1932 when, despite the impressive ratings of the program Flywheel, Shyster and Flywheel (a series that also co-starred brother Leonard “Chico” Marx), it was yanked from the airwaves after one season at the whim of its oil company sponsor. And his 1943-44 series Blue Ribbon Town suffered a similar fate. But, despite these setbacks, Groucho was in high demand as a guest star, making any number of appearances on such shows as Birds’ Eye Open House (with Dinah Shore). Producers were often reluctant to use Marx because he wasn’t a fan of scripted material…but it was Groucho’s ad-libbing that eventually started him on the road to radio’s Top Ten.

The story goes that Bob Hope accidentally dropped his script during a rehearsal for a radio special in 1947, prompting Groucho to follow suit…and what resulted was a wild, freewheeling ad-lib session between the two comic greats. Witnessing this spectacle was producer John Guedel, who was responsible for bringing to radio such hits as People are Funny and House Party (he also convinced a bandleader named Ozzie Nelson that he should think about starting his own program with wife Harriet after their stint on Red Skelton’s program ended). Guedel started to formulate what eventually became You Bet Your Life, which would allow the comedian to interact with members of the audience. “When people were being funny, Groucho could be the perfect straight man,” he later observed. “When the people played it straight, Groucho couldn’t miss with his own comedy.”

Though hesitant at first, Groucho eventually adopted a “what-do-I-have-to-lose?” attitude about the venture, and You Bet Your Life’s audition record sold quickly, securing a sponsor in Elgin-American watches and a berth on ABC’s schedule. It was tough sledding at first: the show was broadcast live in its early days, which often resulted in many uncomfortable slow spots and tepid exchanges between Groucho and the contestants. So Guedel decided to take a page out of the playbook from one of the network’s other hits, Bing Crosby’s Philco Radio Time: they started to record the program. The proceedings would run for a full hour, but would be edited it in half, retaining only the funniest stuff.

During its lengthy radio and television runs, You Bet Your Life’s “quiz” format underwent many changes, but it always involved Groucho interviewing two to three couples during the broadcast, followed by a series of questions that allowed each couple to win a little spending money. (The couple who won the most dough was allowed to play a “bonus round” for even more cash.) If the couple ended up winning no money, quizmaster Marx would give them a little consolation question for a few dollars on the order of “What color is an orange?” (As Groucho would often say, “Nobody leaves here broke.”)

It was also possible to snag a C-note by saying the “secret word.” This word—something common, like “name” or “chair”—would be revealed to the studio and listening audience at the beginning of the show. When it was uttered, the band would strike up a fanfare. (Selected members of the band were “hired” to listen for the secret word, receiving a nice kickback as a result.) When You Bet Your Life came to television, viewers would also see a Groucho-like duck descend from the ceiling.

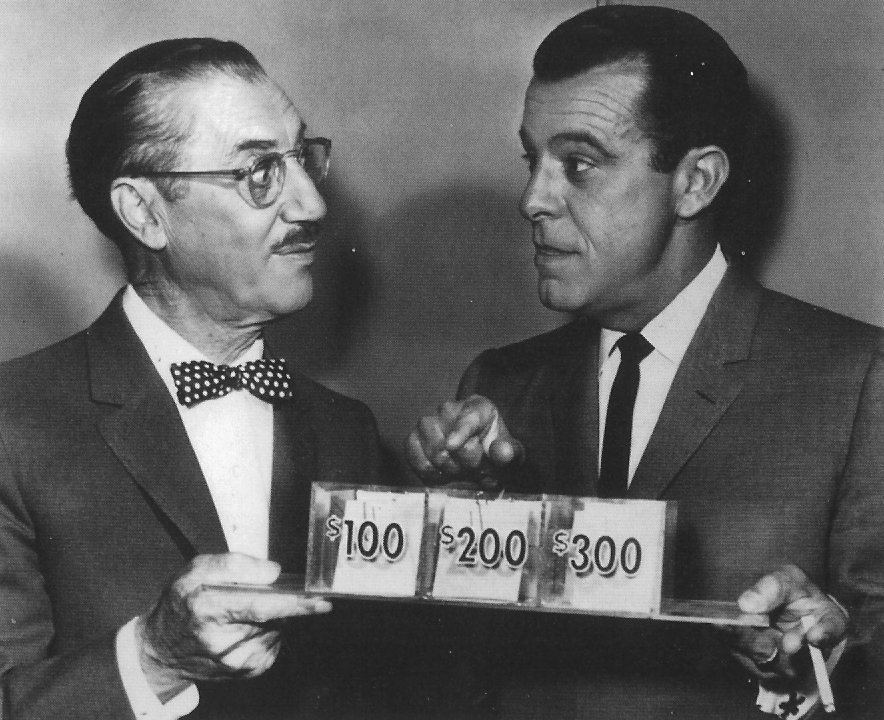

In the early days of You Bet Your Life, Jack Slattery handled the announcing chores…but it wouldn’t be long before Groucho would find his perfect foil in George Fenneman, an actor-announcer whom his boss would later describe as “the male Margaret Dumont.” (This comparison was a tribute to the wonderful character actress who graced so many of the Marx Brothers movies, usually as a stuffy dowager.) George would open each broadcast by sharing that evening’s secret word with the audience. Groucho would then ask, “Really?” “You bet your life!” would be the enthusiastic reply of Fenneman, who would then introduce “the one, the only…GROUCHO!” The band would then strike up Groucho’s theme song, Hooray for Captain Spaulding (from the film Animal Crackers), signaling the start of half an hour of hilarity.

You Bet Your Life ran on ABC for two seasons and moved to CBS in the fall of 1949 (as one of the shows plundered by chairman William S. Paley in his “talent raids”). But NBC would get the last laugh—the show moved to that network in the fall of 1950 and remained a radio staple until 1956. At the same time, the program began its debut on television, and found a home there for eleven seasons, finally giving up the ghost in 1961. It was also on NBC that the show’s best remembered sponsor, DeSoto Motors, paid the bills. For a while, the commercial tagline—“Tell ‘em Groucho sent you”—became a pop culture catchphrase.