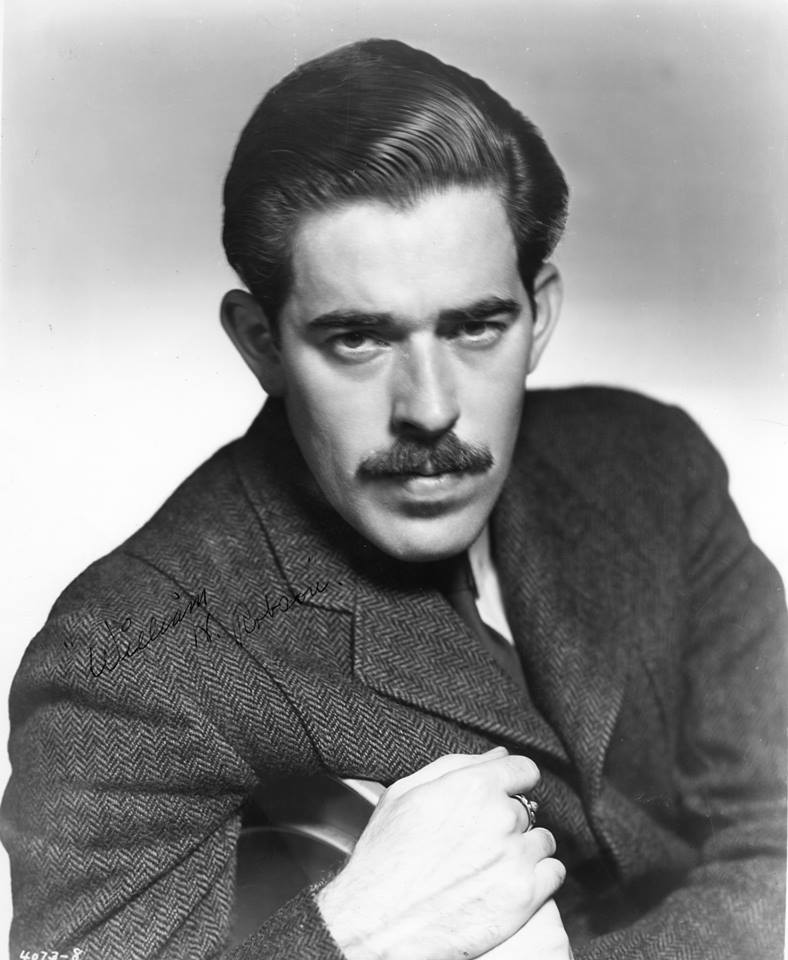

Happy Birthday, William N. Robson!

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on Oct 8th 2016

Though September 30, 1962 is often acknowledged as the date when The Golden Age of Radio ended, director-producer-writer William N. Robson had a decidedly different take in an interview with Dick Bertell in 1976. “The great period of radio was from 1937, ’38 really, through the war,” Robson reminisced. “It was only seven years—the golden age of radio. ‘Suspense’ and ‘Escape’—those are the things one does later because one has all the skills at his fingertips.” Since Robson worked on both Suspense and Escape—not to mention prestigious radio dramas as The Columbia Workshop, The Man Behind the Gun, and The CBS Radio Workshop—he might know what he’s talking about. But we definitely know what we’re talking about when we state that Robson—born in Pittsburgh, PA on this date in 1906—was one of the aural medium’s most amazing talents.

Bill Robson was a Yale man, graduating in 1928 and full of promise. His writing career began with a contract at Paramount Pictures, co-penning the screenplay for a Lee Tracy-Gloria Stuart comedy entitled Private Jones (1933). Robson also started his involvement in radio at the same time in November of 1933 with a CBS West Coast series entitled Calling All Cars, which he wrote and directed. A program that depicted actual crime stories (many years ahead before the celebrated Dragnet), Robson recalled in Leonard Maltin’s The Great American Broadcast a fascinating anecdote about a San Quentin prison break that took place in January of 1935, in which four members of the prison’s Board of Governors were taken hostage by the escapees. Asked via a phone call at 2:30pm to dramatize the incident on Calling All Cars, Bill agreed—thinking he had three days to work up a treatment…

That’s when executive Dick Wiley informed him they had an open hour at 5pm, and since they already had actors and an orchestra rehearsing (for another show) why not do it then? Robson and his team completed a script in time to meet the deadline; with a minute to air the news came down that the real-life escapees had been rounded up (inside a cemetery in Petaluma). This report wouldn’t hit the newspapers until after 8pm, however, prompting a giddy Robson to exclaim: “I had scooped the newspapers!” (“Dramatization of the San Quentin Prison Break” was later redone on The Columbia Workshop in 1936.)

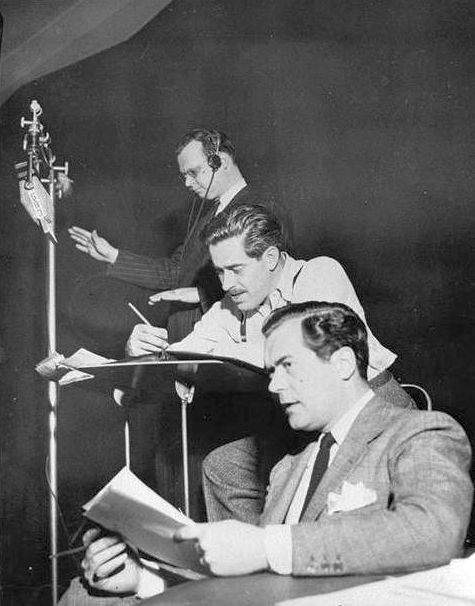

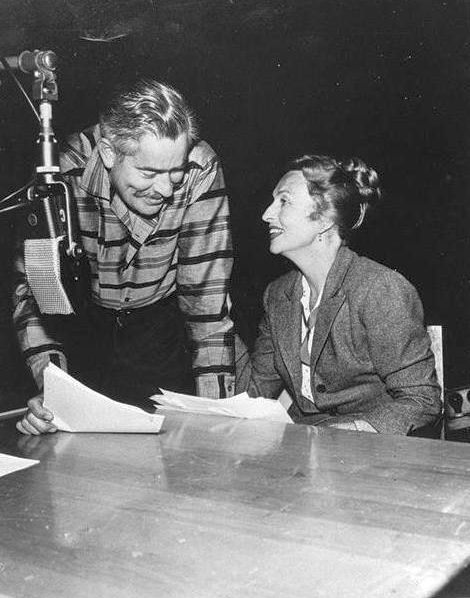

Robson’s work on Calling All Cars won him a friend and admirer in Irving Reis, who suggested Bill move to New York and take over his duties on the innovative and experimental Workshop in 1937. Among Robson’s best-known contributions to Workshop: “S.S. San Pedro” (09/05/37), “Ecce Homo” (05/21/38), “The Story of Radio” (04/17/39), and a September 28, 1939 broadcast of Archibald MacLeish’s famed “The Fall of the City” (previously dramatized on the series in 1937). Bill also directed episodes of Edward G. Robinson’s radio drama Big Town, in addition to working on such programs as Then and Now, The American School of the Air, Americans All—Immigrants All, What Price America, and The Twenty-Second Letter.

In the fall of 1942, William Robson embarked on one of his most prestigious radio series: The Man Behind the Gun, a weekly program that dramatized stories from WW2, ranging from the invasion of Sicily to the Canine Corps. Gun put a human face on the conflict for the listeners at home and featured the work of writers like Ranald MacDougall and Arthur Laurents (later a successful playwright) while utilizing the talents of actors such as Frank Lovejoy, Jim Backus, and Jackson Beck (who narrated many of the broadcasts). Beck had nothing but effusive praise for Robson, calling him “the best director I ever worked for. The word ‘bravura’ was invented for Robson: rough, tough, broad, expansive, a guy who knew what the hell he wanted and knew how to get it.”

Beck’s appraisal for Bill’s work was shared by others: The Man Behind the Gun earned Robson his first George Foster Peabody Award (radio’s equivalent of an Oscar) in 1943, and Bill took home a second trophy that same year for the documentary Open Letter on Race Hatred, which Time magazine called “one of the most eloquent programs in radio history.” Robson’s fine work continued on series like One World, Four for the Fifth, and Doorway to Life (an early attempt to examine the psychological problems unique to children)—yet he wasn’t always driven by prestige series; he wrote and produced one of the medium’s first “adult westerns” in Hawk Larabee, and directed-produced a newspaper comedy-drama starring Mickey Rooney in Shorty Bell.

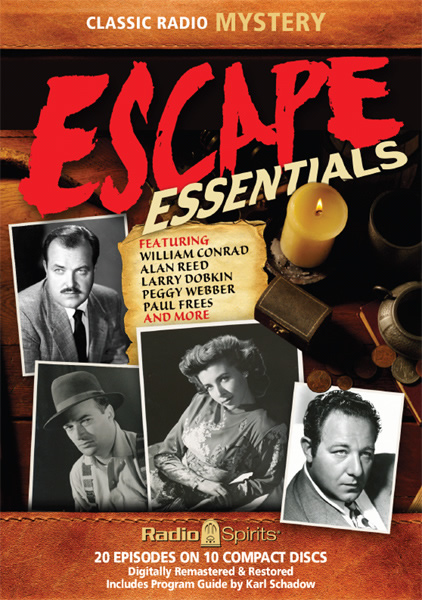

The anthology series “designed to free you from the four walls of today for a half-hour of high adventure” premiered in July of 1947, and William N. Robson was the first director-producer of Escape. (Robson also flexed his writing skills on that show with contributions like “Operation Fleur de Lis” and “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” adapted from the Ambrose Bierce short story.) Bill also directed and wrote broadcasts of Suspense and The Whistler and produced and/or directed such series as Pursuit, Beyond Tomorrow, T-Man, and The Adventures of Christopher London. But because he served as the New York director of the 1947 broadcast Hollywood Fights Back—a blistering rebuttal to the goings-on of the House Un-American Activities Committee—Robson found himself listed among many of his fellow radio artists (including Himan Brown and Mitchell Grayson) in the anti-Communist publication Red Channels. There were other charges leveled against Bill—the man who won a Peabody for The Man Behind the Gun, mind you—but none of them had any real merit. Show business, however, does not adhere to anything resembling logic, and his career stalled for a number of years.

By 1955, apparently all was forgiven. Robson started working again for such shows as Romance (he also returned to Suspense as director-producer from 1956 to 1959) and enjoyed another prestigious assignment in The CBS Radio Workshop (a noble but short-lived attempt to resurrect The Columbia Workshop). Although Bill took on television assignments with scripts for Captain Gallant of the Foreign Legion and Highway Patrol, he remained a creature of radio, directing broadcasts of Luke Slaughter of Tombstone and contributing scripts to another oater, Have Gun – Will Travel (the radio version). Robson would get the last laugh on those who smeared him as a Red; he was chosen by his friend Edward R. Murrow to be the chief documentary writer-producer-director at The Voice of America, where his work garnered him four additional Peabody Awards. William N. Robson departed this world on April 10, 1985 at the age of 88.

The exemplary work of one of radio’s true giants is well represented here at Radio Spirits. You can sample William N. Robson’s genius on the Escape sets Escape Essentials, Escape to the High Seas, and The Hunted and the Haunted, while entertaining yourself with “radio’s outstanding theatre of thrills” in the Suspense collections Around the World, Final Curtain, Ties That Bind, and Suspense at Work. Today’s birthday celebrant is also featured in our Romance compilation, and on Fort Laramie, you can listen to one of that series’ finest episodes in “Never the Twain” (05/06/56), an effective treatise on anti-racism written by Bill himself. Happiest of birthdays to you, Mr. Robson!