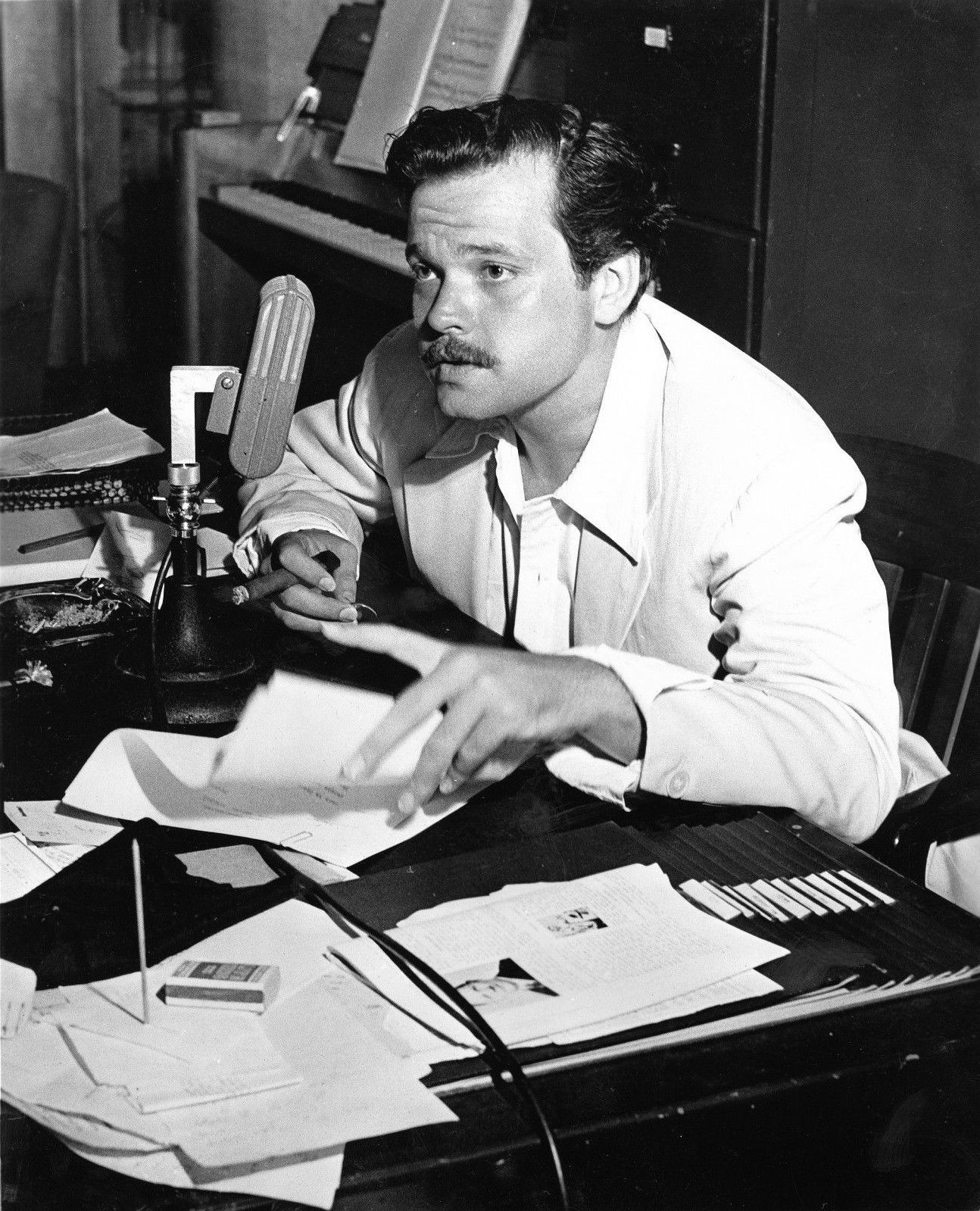

Happy Birthday, Orson Welles!

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on May 6th 2018

Author Gore Vidal once remarked of Orson Welles: “For the television generation he is remembered as an enormously fat and garrulous man with a booming voice, seen most often on talk shows and in commercials where he somberly assured us that a certain wine would not be sold ‘before its time,’ whatever that meant.” But for old-time radio fans, classic movie mavens, and anyone with an interest in nostalgia (not that I’m singling anyone out, you understand), we recognize the individual born George Orson Welles in Kenosha, Wisconsin on this date in 1915 as a true “Renaissance Man.” He was an amazing actor, writer, director, and producer who broke new ground in the worlds of theatre, radio, and motion pictures. Chronicling Welles’ life has never been an easy task; by his own admission, he took great delight in amusing both interviewers and himself by embellishing his personal history. “I don’t want any description of me to be accurate,” Orson once confessed to author Kenneth Tynan. “I want it to be flattering.”

Born in affluence as the youngest son of Richard and Beatrice Welles, Orson experienced much hardship despite his family’s comfortable existence. (His father was quite wealthy, having invented a popular bicycle lamp.) His parents separated when he was four and, upon moving to Chicago, Richard gradually replaced his interest in business with a heavy pull on the bottle. It was up to Beatrice to put groceries on the table, which she did by securing gigs as a pianist. (Orson’s older brother, “Dickie,” had been institutionalized at an early age due to learning difficulties.) Just as the protagonist of Citizen Kane would be separated from his mother, Orson Welles would also experience maternal loss. Beatrice died of hepatitis in 1924. Orson spent three years with Richard, traveling to Jamaica and the Far East. In the words of Frank Brady (author of Citizen Welles): “During the three years that Orson lived with his father, some observers wondered who took care of whom.” Welles’ father died of alcoholism when Orson was fifteen, and the young man never completely forgave himself…believing he was in some way responsible.

The roots of Orson Welles’ desire for a career in the performing arts were well established in this tumultuous time. His interests were encouraged by a combination of factors — including his mother’s musical talents, a summer stay with an artists’ colony after her death, and schooling at the Todd Seminary for Boys (a private institution in Woodstock, Illinois). It was there that Orson met his mentor and lifelong friend, Roger Hill, who indulged his creative pursuits while nurturing his academic interests. The Todd Seminary had a radio station, and it was there that Welles made his debut over the ether, performing in a production of Sherlock Holmes that he wrote.

Orson graduated in 1931 and, despite obtaining a scholarship to attend Yale University, he elected to embark on a life of travel — buoyed by both his inheritance from his father and an interest in painting. After a walking tour of Ireland, he decided to apply a bit of blarney and strode into Dublin’s Gate Theatre, claiming to be a Broadway star. His age (sixteen) naturally set off skepticism, but Orson soon proved his mettle by acting in small roles in various Gate Theatre productions (notably a version of W. Somerset Maugham’s The Circle at Dublin’s Abbey Theatre). Orson Welles’ rise in the world of theatre was truly meteoric. Meeting Thornton Wilder at a party in Chicago got him an introduction to Alexander Woollcott…and that led to a job with Katherine Cornell’s repertory company, where he appeared in such plays as Romeo and Juliet and The Barretts of Wimpole Street.

His role as Tybalt in Romeo and Juliet garnered the attention of John Houseman, his future Mercury Theatre partner, who cast Orson in the lead of Archibald MacLeish’s Panic. Welles would perform a scene from Panic when he made his debut on the CBS Radio series The March of Time. The wunderkind had made his official debut over the airwaves in 1934 on The American School of the Air (thanks to actor-director Paul Stewart, another lifelong Welles crony). He soon began standing regularly in front of a microphone on such series as The Columbia Workshop, The Cavalcade of America, and America’s Hour. One of his best-remembered radio gigs was briefly portraying Lamont Cranston, the “wealthy young man about town” whose secret identity was…The Shadow.

On stage, Orson Welles and John Houseman scaled new heights in theatre with their participation in The Federal Theatre Project, where they staged such productions as an all-black version of Macbeth and the now-legendary The Cradle Will Rock. The two men went on to form The Mercury Theatre, where they continued to find new ways to be audacious — including a modern-dress version of Julius Caesar. Much of Orson and John’s Mercury work was done simultaneously with The Mercury Theatre on the Air. This CBS anthology (originally entitled First Person Singular) began on July 11, 1938 and dramatized classic works of literature. October 30, 1938 marked the day that Orson Welles would find his instant fame with his production of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. Presented in the novel form of news bulletins breaking into a musical program, the episode later acquired mythical status by allegedly frightening listeners who were unaware that they were listening to a work of fiction. “The War of the Worlds” would bring Welles to the attention of Hollywood. After signing a contract with RKO Pictures in August of 1939, Orson commuted back-and-forth from East to West Coast as Mercury Theatre continued on the air (the title of the program became Campbell Playhouse in December of 1938) until March 31, 1940.

It was Orson Welles’ third “proposal” to RKO that would go before the motion picture cameras — a film that is often named in “ten best” movie lists and, for some, remains the greatest motion picture ever made —Citizen Kane (1941). Despite being what could be arguably called his greatest achievement, Kane also became Welles’ cinematic downfall. The rich, fascinating tale of a newspaper mogul, Kane purportedly contained so many parallels to the real life of William Randolph Hearst that Welles and RKO became frequent targets of Hearst’s papers. Hollywood, under pressure from Hearst, began distancing itself from the twenty-six-year old wunderkind. In fact, it’s been speculated that Welles’ second film for the studio, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), might have surpassed the greatness of Citizen Kane had Welles not been so preoccupied with making a movie in Mexico…leaving the studio free to edit Ambersons against his wishes.

Orson Welles would eventually be fired by RKO, and from then on his motion picture career was defined by a series of assignments at various studios. Unfortunately, no one would commit to signing the director to a long-term contract because of his troubles at RKO…and because his desire to maintain creative control led him to acquire an undeserved reputation for irresponsibility. Orson made such films as The Lady from Shanghai (1948) for Columbia and Touch of Evil (1958) for Universal-International, but most of his pictures were the working definition of what we would call “independent filmmaking.” It took him three years to make his version of Shakespeare’s Othello (1951) — during which time, he funded the production with the money from acting jobs. My personal favorite of Welles’ attempts to bring Shakespeare to the silver screen is a 1948 version of Macbeth, which he put together at Republic Studios. (The idea of using the place famous for B-westerns and cliffhanger serials just makes me giggle for one reason or another.)

Despite his motion picture career, Orson Welles never abandoned radio. In the 1940s, he hosted such programs as The Orson Welles Theatre, Hello Americans (Ceiling Unlimited), Orson Welles’ Radio Almanac, This is My Best, and The Mercury Summer Theatre. Welles made several memorable appearances on “radio’s outstanding theatre of thrills,” Suspense, and guested on the likes of Command Performance, G.I. Journal, The Gulf Screen Theatre, Information Please, The Lux Radio Theatre, Mail Call, and The Silver Theatre. Orson performed alongside such radio personalities as Gracie Fields, Dinah Shore, and Rudy Vallee. He poked fun at himself (calling his radio persona “Crazy Welles” or “Imperial Welles”) with the likes of Fred Allen, Jack Benny, Edgar Bergen & Charlie McCarthy, Bob Hope, and Danny Kaye. Much of Welles’ Othello money came from his regular gigs as the star of The Lives of Harry Lime (reprising the famous character he portrayed in the 1949 movie classic The Third Man) and narrator of The Black Museum, both of which were broadcast in 1951 and 1952.

My favorite Orson Welles anecdote has a lot to do with radio. He had a reputation for being a bit undisciplined—performances of his plays would sometimes be postponed, and he was always scrounging here and there to raise money for a movie. Richard Wilson, an assistant to Orson during his Mercury Theatre radio days, reminisced: “Radio was the only medium that imposed a discipline that Orson would recognize, and that was the clock. When it came time for Mercury to go on the air, there was no denying it. I can’t think of one theater production…that was not postponed, but [in] radio, he knew every week that clock was ticking, that red light [would come] on and say ‘On the Air.’ And good or bad, right or wrong, boy, that was it. It was the only discipline Orson was able ever to accept.” Orson Welles left this world for a better one at the age of 70 in 1985.

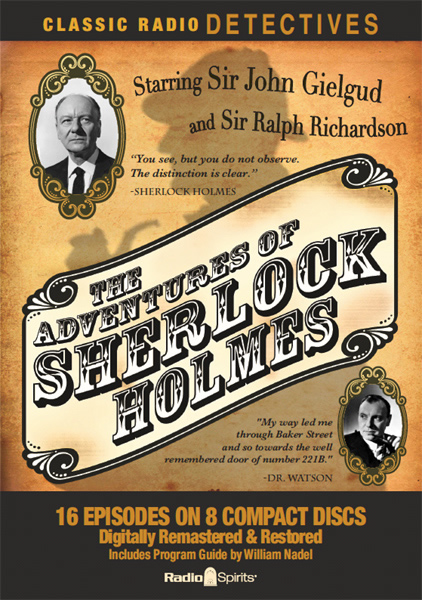

To celebrate one of the true greats (sorry for gushing…I’ve always been a big fan), Radio Spirits recommends you check out The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, a collection of broadcasts from the 1955 BBC radio series, features Orson as Professor Moriarty, Holmes’ nemesis (“The Napoleon of Crime”). Welles is one of several celebrities featured in the biographies that comprise the DVD set Hollywood’s Greatest Screen Legends, and you’ll also find him in our 10-DVD set of films dealing with space travel, NASA Collection. Last—but certainly not least—enjoy a dramatization of Orson’s early days of launching the Mercury Theatre in Richard Linklater’s delightful 2008 feature film—Me and Orson Welles.