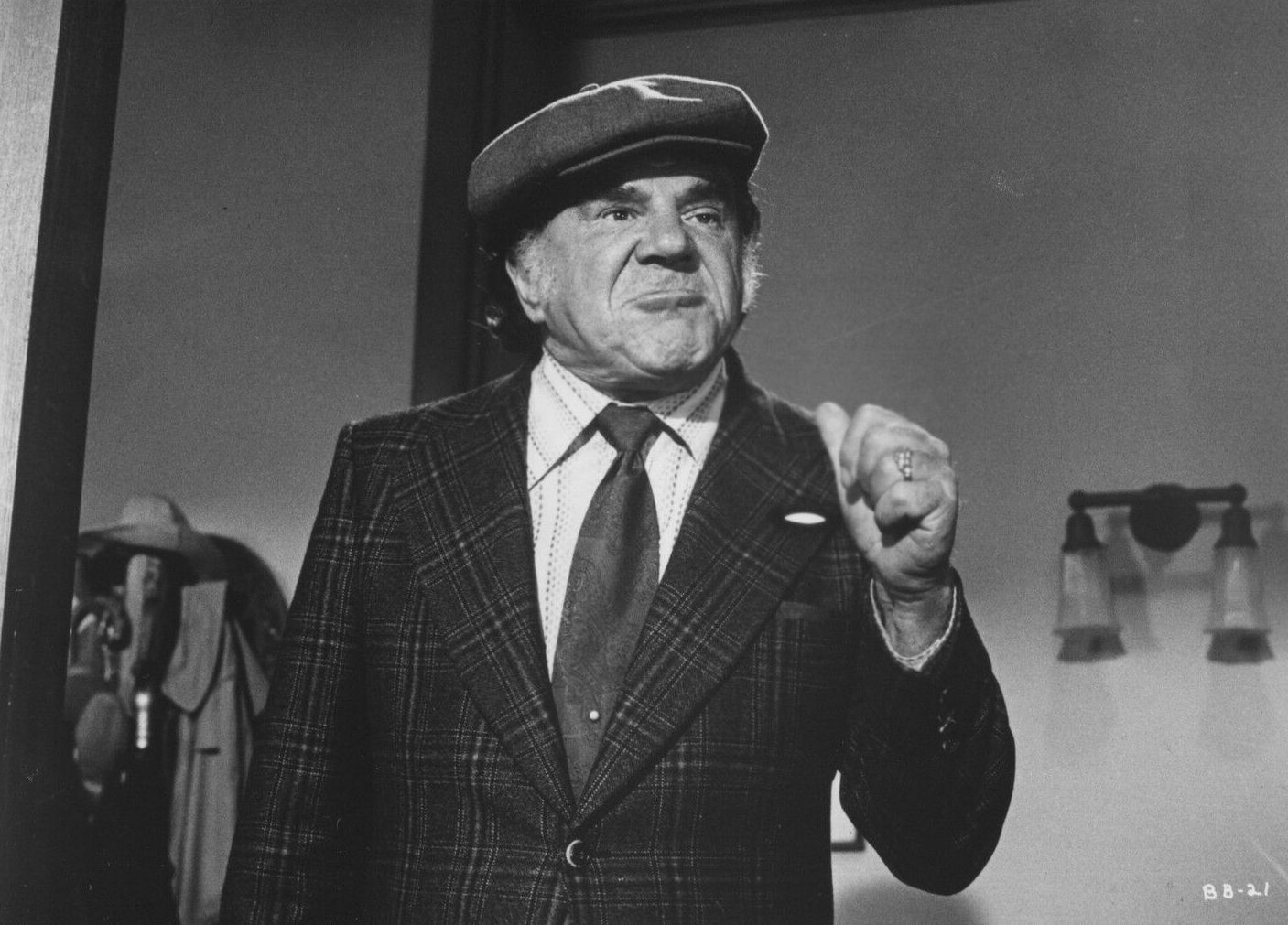

Happy Birthday, Lionel Stander!

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on Jan 11th 2020

Lionel Stander, the character actor best remembered by fans as chief-cook-and-bottle-washer Max on the TV detective drama Hart to Hart, also had a lengthy radio career—notably playing “stooge” to Fred Allen on The Hour of Smiles and Town Hall Tonight in the 1930s. Stander—born in The Bronx on this date in 1908—used his trademark gravelly voice and skill with dialects (he was the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants) to become a valued member of “The Mighty Allen Art Players.” But Lionel had some deficiencies in the “on-time-for-rehearsals” department; he was late so often that Fred joked his employee was probably preoccupied with printing pamphlets in his apartment. This was a reference to Stander’s leftist politics—Lionel Stander was a pro-labor activist at a time when such beliefs could get a performer blacklisted…and in Stander’s case, they did. However, his later success on Hart to Hart also allowed him to get the last laugh.

Lionel Stander’s 1994 obituary in The New York Times noted that “he attended everything from the Little Red Schoolhouse to military and prep schools,” but also that he never graduated from any of them. In addition, he briefly attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill while working as a newspaper reporter in Charlotte. (At UNC Stander appeared in a pair of student dramatic productions.) His acting career, he later confessed, came about because a role in e e cummings’ Him required someone capable of shooting craps, at which the reluctant thespian was quite skilled. From this debut, Stander went on to a number of productions staged on Broadway, notably Singing Jailbirds, Red Rust, and The House Beautiful. (Dorothy Parker memorably tagged the latter “the play lousy”).

Many stage performers in New York were able to find additional work in movie shorts produced by the Vitaphone Studio, and Lionel Stander was no exception. He worked with such comedians as Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle (In the Dough [1933]), Jack Haley (Salt Water Daffy [1933]), Shemp Howard (Smoked Hams [1934]), and Bob Hope (The Old Grey Mayor [1935]). At the same time, Lionel was also making inroads in the aural medium with his work for Fred Allen and Eddie Cantor. (Stander was one of several actors who used a Russian dialect to play Cantor violinist Dave Rubinoff…who suffered from mike fright). His radio work, he later recalled, led to his hiring at RKO as a Russian dialectician (it took a while before producers realized he was an English-speaking actor).

A nice showcase in the 1935 Noel Coward film The Scoundrel was the catalyst for Lionel Stander getting more movie work, including Hooray for Love (1935), We’re in the Money (1935), If You Could Only Cook (1935), and The Milky Way (1936). He was under contract to Columbia Pictures, who cast him in the classic 1936 comedy Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. They also used him as legman “Archie Goodwin” in the studio’s two Nero Wolfe films, Meet Nero Wolfe (1936) and The League of Frightened Men (1937). (Lionel would reprise not only his role in Deeds but a part in A Star is Born [1937] when both films got the Lux Radio Theatre treatment in 1937.) Stander continued his radio appearances on shows headlined by Bing Crosby and Al Jolson, but his commitment to political causes (like raising money for the Scottsboro Boys and the Spanish Loyalists) started to get him unwanted attention in Tinsel Town. Because Lionel supported the Conference of Studio Unions—which was engaged in a bruising fight with the mob-connected International Alliance of Stage Employees (IATSE)—Columbia head Harry Cohn labeled him a “Red” and suggested that the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) fine any studio who renewed Stander’s contract.

Although the House Un-American Activities Committee is often associated with the 1950s and the ”McCarthy era,” HUAC really had its origins back in the late 1930s as a special committee investigating “Reds” in the motion picture industry. Lionel Stander was among the first performers to fall under the HUAC microscope (along with Fredric March, James Cagney and several others). Lionel would later be publicly cleared of any Communist activity by a district attorney after “secret” grand jury testimony was publicly published in 1940, but since suspicion by HUAC remained, there was a three-year stretch before his next movie gig. Radio was a bit more accommodating. 1941 briefly found Stander as the star of The Life of Riley—not the better-known William Bendix vehicle, but an entirely different sitcom (Lionel’s character was named “J. Riley Farnsworth”). Lionel later became a cast member on The Danny Kaye Show (1945-46) as a character jokingly referred to as “the sandpaper Sinatra.” (Stander appeared with Danny in the 1946 comedy The Kid from Brooklyn, which also featured Eve Arden—also a Kaye Show cast member.) Stander made regular appearances on such shows as The Mayor of the Town and Joan Davis Time, and rounding out his radio resume are credits like Crime Does Not Pay, Favorite Story, Forecast, G.I. Journal, The Gulf Screen Guild Theatre, The Jack Paar Program, The Lincoln Highway Radio Show, The Rudy Vallee Sealtest Show, and Stage Door Canteen.

Lionel Stander had nothing but praise for director Preston Sturges, who cast him in films like The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (1947) and Unfaithfully Yours (1948). If not for Sturges, Lionel’s sole source of income would have been contributing voices to Walter Lantz cartoons (you’ll hear Stander in several Woody Woodpecker shorts as “Buzz Buzzard”). Stander was among the many show business personalities listed in the pamphlet Red Channels, and when actors Larry Parks and Marc Lawrence “named” Lionel in their testimony before HUAC, Stander demanded the opportunity to clear his name. (Lionel later tried to sue Lawrence for slander but was informed that Marc had congressional immunity.) When Stander finally appeared before HUAC on May 6, 1953, he insisted that the TV lights and cameras be turned off, declaring “I only appear on TV for entertainment or for philanthropic organizations and I consider this a very serious matter that doesn’t fall into either category.” Stander didn’t hold back with regards to his testimony before the committee: “I am not a dupe, dope, mope, moe or shmoe. I was absolutely conscious of what I was doing, and I’m not ashamed of anything I ever said in public or in private.”

Lionel Stander took a heroic stand…but it cost him his role in the road company version of Pal Joey, with influential red-baiters (like Walter Winchell) putting pressure on the producers to fire Stander. (Lionel later quit the show to save them the aggravation). He did land the occasional film job (he’s the narrator for the 1961 neo-noir Blast of Silence and he has a nice turn in The Loved One [1965]), as well as a nice Broadway gig (The Conquering Hero, Luther). However, he had better luck in Europe, where his film resume included such features as Cul-De-Sac (1966), A Dandy in Aspic (1968), and Once Upon a Time in the West (also 1968). In the 1970s, Lionel began making appearances in American films like New York, New York (1977) and 1941 (1979)…but it was Robert Wagner (who had given Stander a rare working gig in a 1968 episode of Wagner’s TV series It Takes a Thief), who insisted that Stander be cast as “Max” on Hart to Hart. (For his work on the show, Lionel won a Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor—Series, Miniseries or Television Film in 1983.) He would go on to reprise his role from the series in five Hart to Hart TV-movies before his death of lung cancer in 1994.

Radio Spirits invites you to experience today’s birthday boy in his signature role as Max in the DVD boxset Hart to Hart: Movies are Murder Collection. There were eight TV movies produced for TV between 1993 and 1996 after the success of the 1979-84 original, and Lionel Stander appears in the first five. You can also hear Lionel in “A Piece of Pie,” a 1946 audition for what eventually became The Damon Runyon Theatre in the collection It Comes Up Mud. Happy birthday, Lionel!