Happy Birthday, Groucho Marx!

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on Oct 2nd 2017

If comedian Groucho Marx—born Julius Henry Marx in New York City on this date in 1890—had achieved his childhood ambition of becoming a doctor…well, the world would know a little less laughter. Fortunately for audiences who enjoyed the quick, insulting wit of the premier funnyman in movies, radio, and TV, Julius was “persuaded” to go into show business by his domineering mother Minnie, who believed that he and his brothers—collectively known as Leonard (Chico), Adolph (Harpo), Herbert (Zeppo), and Milton (Gummo)—were destined to conquer the show business world. Although the term “stage mother” often conveys negativity, we owe Mother Minnie a debt of gratitude for riding herd on her “boys.”

Stories differ on just why young Julius was discouraged from pursuing a medical career; one account states that he was needed to supplement the family’s income (his father Sam—known to the family as “Frenchie”—never really achieved success in the tailoring business), while another puts the blame on his limited formal education. Minnie herself had a tenuous connection to show business in that her father had once made a living as a traveling magician and her brother Al (Shean) Schoenberg was one-half of the popular vaudeville duo, Gallagher and Shean. Julius’ first show business job was with a singing trio that paid a handsome $4-a-week. Unfortunately, a member of that group made off with Julius’ salary and left him stranded in Colorado—he had to work a series of odd jobs to earn his fare back home.

Julius would have better luck letting Minnie run the show; in 1909, she put together a quartet consisting of Julius, Adolph (who changed his name to Arthur), Milton, and non-Marx brother Lou Levy. Collectively they were known as “The Four Nightingales,” and for several years the brothers got by as an average vaudeville act. It was only during a particularly dismal performance in Nagadoches, Texas when the Marxes discovered that they had a flair of comedy; they started heckling the audience giving them grief during their act…and the crowd ate it up.

The Brothers Marx took an old comedy routine from Gus Edwards, “School Days,” and refashioned it as “Fun in Hi Skule”—an act that they dutifully performed to appreciative laughter over the years until eventually they arrived at the Mecca of Vaudeville, The Palace Theatre, in 1919. Along the way, the group started to develop their characters (Chico the phony Italian, Harpo the silent sprite) and their nicknames, bestowed upon them by fellow performer Art Fisher during a card game. Julius would go by “Groucho” for the rest of his career, and the Marx Brothers went on to conquer Broadway with three smash stage hits: I’ll Say She Is (1924), The Cocoanuts (1925), and Animal Crackers (1930).

If those last two production sound vaguely familiar, it’s because they were the first two films featuring the Marx Brothers when they began making movies for Paramount in 1929. The team would follow those successes with Monkey Business (1931), Horse Feathers (1932)…and the film many consider to be their finest screen comedy, Duck Soup (1933). All five of those films featured Groucho, Chico, Harpo, and Zeppo (Gummo quit performing after he was drafted in World War I), and when the siblings were hired by MGM to make A Night at the Opera (1935), Zeppo had quit the motion picture business as well. The three Marx Brothers followed the giant success of Opera with ADay at the Races (1937), and later made three additional films for Leo the Lion: At the Circus (1939), Go West (1940), and The Big Store (1941). The three remaining movies featuring Groucho, Chico, and Harpo were Room Service (1938; RKO), A Night in Casablanca (1946; United Artists), and Love Happy (1949; also UA)—though Groucho’s participation with Chico and Harpo in this last production is rather fleeting.

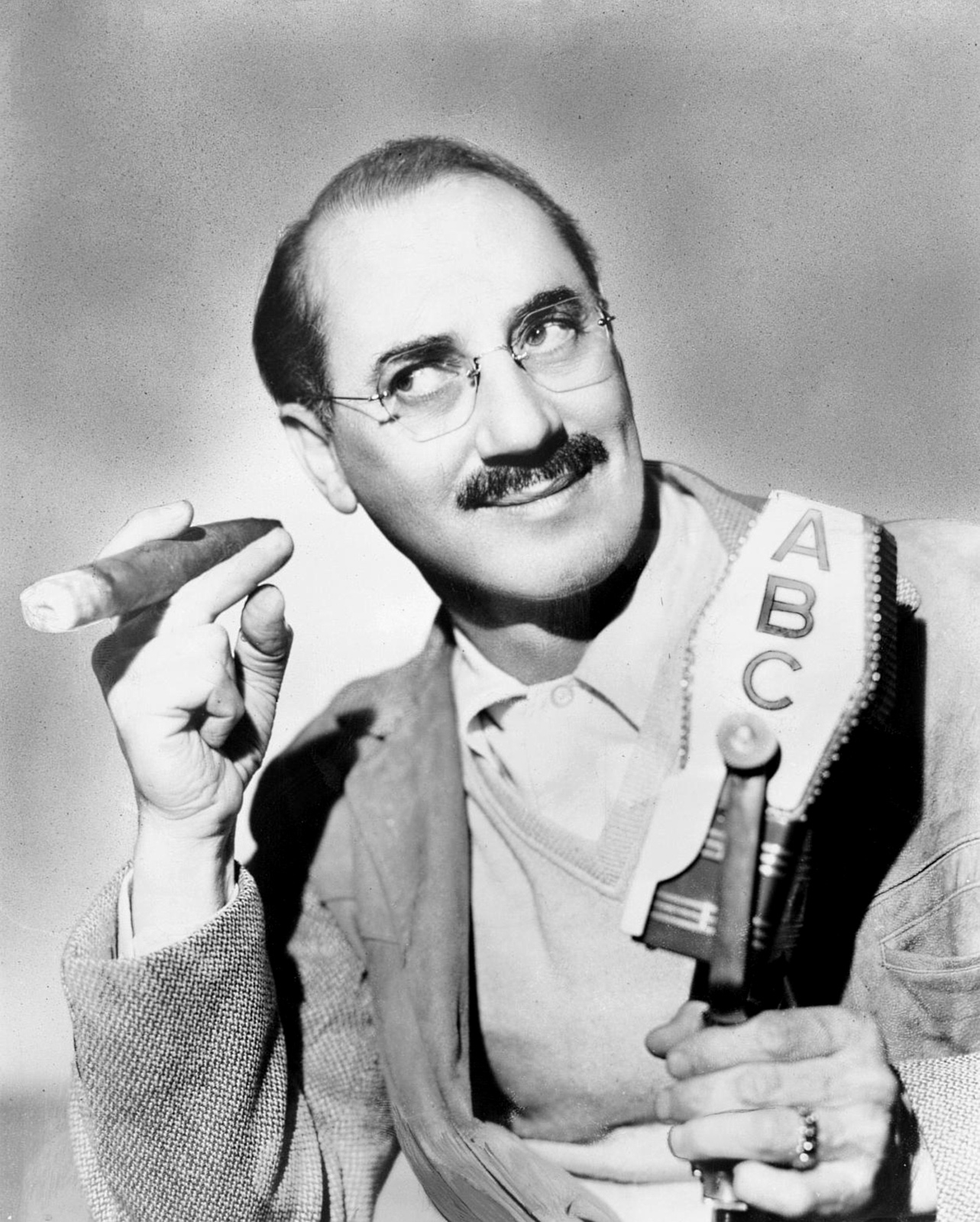

In the Marx Brothers’ films, Groucho handled most of the verbal comedy; in his trademark glasses and greasepaint eyebrows-and-moustache, he’d sidle up to wealthy dowagers (generally played by favorite foil Margaret Dumont) and let loose with a barrage of rapid, cut-to-the-quick insults—in fact, his entire character was built on a foundation of defying authoritarian figures and deflating pomposity. In 1932, he and Chico took a stab at radio with a comedy program over NBC Blue entitled Flywheel, Shyster and Flywheel (Harpo did not appear, owing to the silent nature of his comedy). The series did well in the Hoopers, but sponsor Standard Oil was disappointed that it didn’t match the audience of Texaco’s The Fire Chief Program (with Ed Wynn), and pulled out after one season.

Groucho and Chico would later join the all-star cast (Cary Grant, Carole Lombard, etc.) of NBC’s The Circle in January of 1939, later described by the show’s writer Carroll Carroll as “radio’s most expensive failure.” In subsequent radio ventures, Groucho went solo…without much success. He was the host of CBS’ Blue Ribbon Town from 1943-44, a show that surviving broadcasts reveal isn’t quite as bad as its reputation (Groucho got solid support from regulars like Virginia O’Brien, Leo Gorcey, Fay McKenzie, and Kenny Baker—who inherited the program after Marx left in June of 1944). Groucho was depressed that radio popularity eluded him despite getting appreciative laughs while guesting on shows headlined by the likes of Rudy Vallee, Eddie Cantor, Jack Benny, and Dinah Shore (Marx was practically a regular on Dinah’s Birds Eye Open House). Even his good friend Irving Brecher couldn’t create a hit for the acerbic funnyman; a pilot entitled “The Flotsam Family” flopped (though Brecher later refashioned it into The Life of Riley for William Bendix).

An appearance on a Walgreens’ special would be the catalyst for Groucho’s eventual radio success. As Groucho and host Bob Hope deviated from a prepared script with some fast-and-furious ad-libs, producer John Guedel (the man behind People are Funny) was convinced he had the perfect radio format for Marx. Groucho would host a quiz show—which eventually became You Bet Your Life—and exercise his talent for sharp wisecracks “interviewing” the contestants. Marx was reluctant, to say the least; he believed that playing the role of “quiz show host” was a considerable comedown. But as he gradually grasped that You Bet Your Life’s “quiz” was merely a backdrop for allowing him to do what he did best—improvised conversation—he enthusiastically embraced the project. You Bet Your Life premiered over ABC Radio on October 27, 1947 for Elgin-American watches and quickly became one of the fledgling network’s big hits. It later transitioned to CBS in October of 1949 for a season and then moved into its permanent home on NBC a year later. Because of the simplicity of its format, You Bet Your Life was broadcast simultaneously on radio and TV (where it quickly made a nest in the Top Ten of the Nielsen ratings); the radio version bowed out on June 10, 1960, but the boob tube incarnation lasted one additional season (and was retitled The Groucho Show).

Before his death on August 19, 1977 at the age of 86, Groucho Marx continued to be a beloved TV presence, both as a guest on the medium’s many talk shows and appearances on variety hours like The Hollywood Palace and The Kraft Music Hall. He’s revered by students of comedy for his take-no-prisoners wit, and his quotable lines (like “I refuse to join any club that would have me as a member”) are cherished by those who took pleasure in Groucho’s fearless mockery of society’s conventions. Radio Spirits invites you to enjoy Groucho on radio in our Jack Benny & Friends collection, as the birthday boy trades quips with Jack on a February 20, 1944 broadcast. The 3-DVD set Groucho Marx TV Classics presents the comedian at his finest with a compendium that includes telecasts from You Bet Your Life and The Hollywood Palace, and the Marx Brothers TV Collection not only features Groucho but brothers Chico and Harpo in clips from fifty rare and vintage television appearances. Finally, we recommend you peruse the Radio Spirits bookshelf until you locate Marx & Re-Marx; written by Andrew T. Smith, it’s a fascinating history of Groucho and Chico’s “lost” radio show, Flywheel, Shyster and Flywheel—with the scripts from the original series and the story of how they came to be revived by BBC Radio in the early 1980s. If Groucho were here, he might say, “Outside of a dog, a book is man’s best friend. Inside of a dog it’s too dark to read.”