Happy Birthday, Claude Rains!

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on Nov 10th 2022

Claude Rains—born William Claude Rains in Clapham, London, England on this date in 1889—made his American film debut in one of the classic Universal Pictures horror films of the 1930s: The Invisible Man. You don’t see Rains until the very end of the movie…owing to the fact that his character of Dr. Jack Griffin is the transparent individual referenced in the film’s title. In fact, when Rains had his first screen test after signing with Universal in 1932, he did rather poorly…and he himself called the tryout “the worst in the history of moviemaking.” This mattered very little to Man’s director, James Whale, who hired Claude anyway on the strength of Rains’ mellifluous baritone. “I don't care what he looks like,” declared Whale, “that's the voice I want.”

Claude Rains’ father, Frederick William Rains, was a stage actor by trade and

so it was probably foretold in the cards that young Claude—nicknamed “Willie

Wains” because of his heavy Cockney accent and slight stutter—would do the

same. Acting was not particularly lucrative for the Family Rains; Claude grew

up in the slums and of the twelve children born to Frederick and wife Emily,

all but three died of malnutrition. Emily took in boarders to help with the

family’s finances, but it wasn’t enough: Claude left school after his third

year in order to sell newspapers.

Because of his father’s chosen profession, Claude Rains spent a good deal of time in the theatre and at the age of ten made his stage debut in Sweet Nell of Old Drury. Rains began his career as a call boy (the individual responsible for telling the actors they were due on stage) and would eventually work his way up with stints as a prompter, stage manager, and understudy before getting small parts in productions and eventually larger acting showcases. In 1912, Claude emigrated to the United States in the hopes of finding more work in New York theatres.

Claude Rains returned to his native England in 1914 at the outbreak of World War I in order to do his part by serving in the London Scottish Regiment. He was in some fine company; among his fellow soldiers were Ronald Colman, Cedric Hardwicke, Herbert Marshall, and Basil Rathbone. Just as Marshall sustained a leg injury that left him with a prosthetic limb and limp for the rest of his acting career, Rains would lose 90 percent of the vision in his right eye after experiencing a gas attack at Vichy. Claude was dismissed from combat as a result, though he continued to serve in the Bedfordshire Regiment, advancing to the rank of captain.

The end of the war allowed Claude Rains to return to acting, and at the urging of Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree—the founder of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA)—took elocution lessons (which Tree paid for) to lose his Cockney accent. Rains became an acting instructor at RADA, where he taught individuals like John Gielgud (who had nothing but praise for his teacher, noting in a TCM interview that he “learnt a great deal about acting from this gentleman”) and Charles Laughton. It was about this time that Claude made his official motion picture debut, in a British silent entitled Build Thy House (1920).

Claude Rains’ theatrical career flourished in

England, where he graced such productions as Ulysses S. Grant and The

Rivals. He returned to the U.S. in 1927, where future acclaim in such

Broadway triumphs as The Apple Cart, The Constant Nymph,

and The Good Earth awaited him. (Claude eventually won a Tony

in 1951 for his acting work in Darkness at Noon.) His success

in The Invisible Man led to roles in “Universal horrors”

like The Man Who Reclaimed His Head (1934) and Mystery

of Edwin Drood (1935), but Rains’

silver screen posterity wouldn’t really take hold until he signed with Warner

Bros. in 1935 and was cast in 1936’s Anthony Adverse. Claude

found his niche portraying sophisticated villains in such features as The

Prince and the Pauper (1937) and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938).

(The legend goes that Rains did a subtle lampoon of fellow Warners stablemate

Bette Davis—who nevertheless considered the actor her favorite co-star—to

portray the fey Prince John.)

On loan to Columbia Pictures, Claude Rains portrayed the fatally corrupt

Senator Joseph Paine in the Frank Capra-directed Mr. Smith Goes to

Washington (1939)...and for his fine performance, received the first of

four Best Actor in a Supporting Role nominations from the Academy of Motion

Picture Arts and Sciences. Rains would also be nominated for Casablanca

(1942; probably his best remembered screen turn among classic film fans, as

“poor corrupt official” Captain Louis Renault), Mr. Skeffington (1944),

and Notorious (1946). Despite all those nominations…Claude Rains never

won an Oscar. But he left behind a wealth of extraordinary motion picture

performances, among them They Won’t Forget (1937), Four Daughters (1938),

The Sea Hawk (1940), Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941), The Wolf Man

(1941), Kings Row (1941), Now, Voyager (1942), Phantom of the

Opera (1943), Angel on My Shoulder (1946), and Lawrence of Arabia

(1962).

Claude Rains’ motion picture success quite naturally led to multiple radio

appearances on such anthology programs as The Cavalcade of America,

The Ford Theatre, Lincoln Highway, The Lux

Radio Theatre, The Philco Radio Hall of Fame, The

Radio’s Reader’s Digest, Stagestruck, Suspense,

and The Theatre of Romance. Rains did critically acclaimed work

on Columbia’s Shakespeare (a.k.a. The Shakespearean Cycle),

headlining a broadcast of Julius Caesar (with Raymond Massey) and This

is War!, with the March 21, 1942 broadcast of “You’re On Your Own.” In

a brief story arc on Doctor Christian in 1945, Rains filled in

(as “Dr. Alexander Webb”) for star Jean Hersholt when Hersholt took a brief

trip to his native Denmark. Claude’s most notable radio gig was as the star of The

Jefferson Heritage, a 13-week series recorded by the National

Association of Educational Broadcasters for syndication in 1952. Rains was also

a guest star on shows headlined by Fred Allen (The Texaco Star Theatre),

Tallulah Bankhead (The Big Show), and Rudy Vallee (The

Flesichmann’s Yeast Hour, The Royal Gelatin Hour) and on

the likes of Inner Sanctum Mysteries.

Although by the 1950s/1960s Claude Rains’ film appearances had narrowed

somewhat (he appeared in the likes of This Earth is Mine [1959], Twilight

of Honor [1963], and The Greatest Story Ever Told [1965], his

cinematic swan song) he was still working on the small screen with multiple

guest appearances on Alfred Hitchcock Presents and credits on

such TV favorites as Dr. Kildare, Naked City, Playhouse

90, Rawhide, Sam Benedict, and Wagon

Train. Although he had hoped to complete the memoirs he was working on

at the time of his death, Claude Rains left this world for a better one in 1967

at the age of 77. His daughter Jennifer (whose stage name was changed to

Jessica) observed: “And, just like most actors, he died waiting for his agent

to call.”

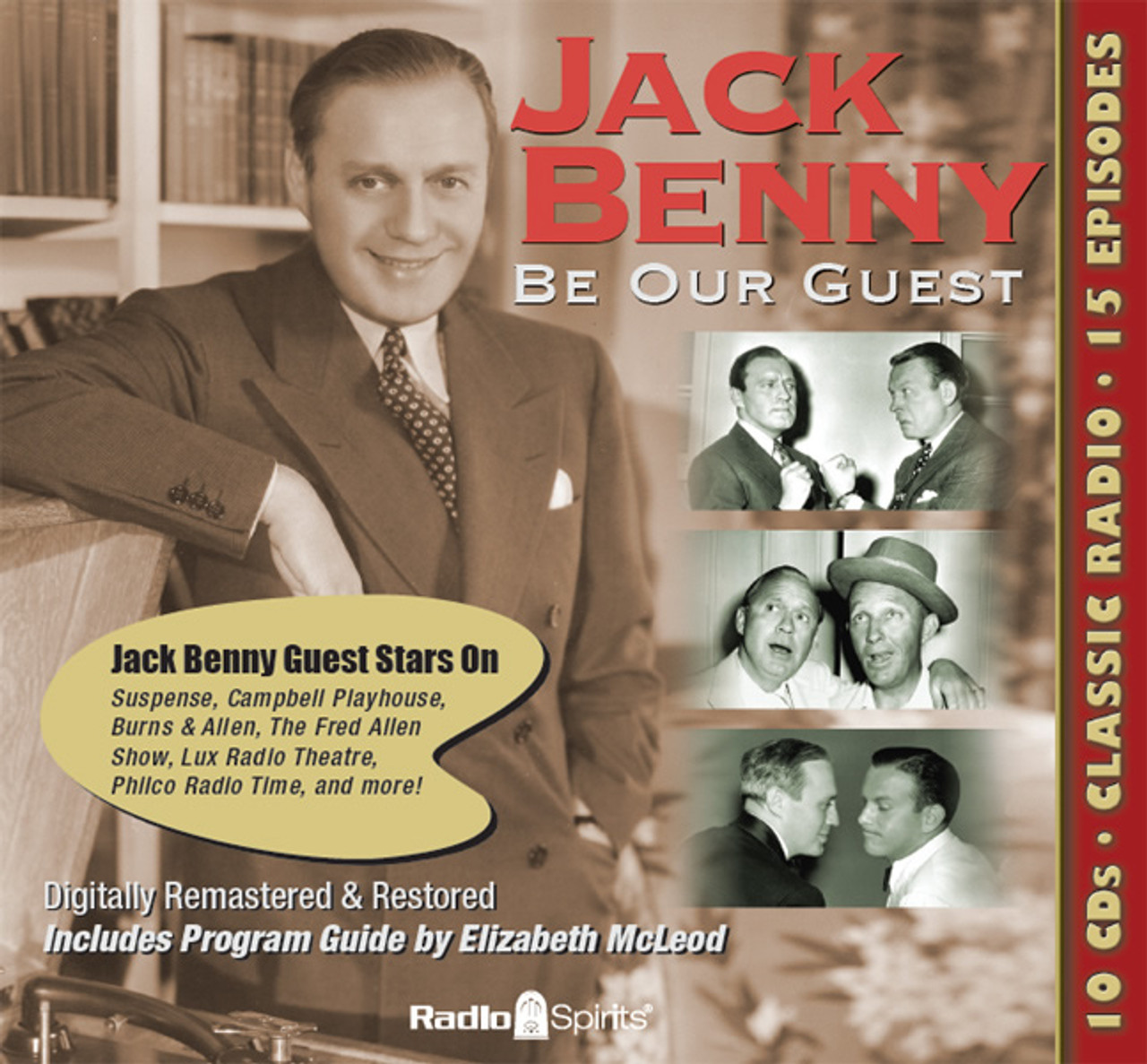

“There was somebody who taught me a very great deal at drama school, and I am certainly grateful to him for his kindness and consideration,” Sir John Gielgud once mused in an interview. “His name was Claude Rains. I don't know whatever happened to him. I think he failed and had to go to America.” I’m sure Sir John’s tongue was firmly in his cheek when he made these remarks but as an admirer of Claude Rains’ work in films I’d say we made out best on the deal. Our birthday boy appears in The Ford Theatre’s March 4, 1949 presentation of “The Horn Blows at Midnight,” which is available on our Jack Benny collection Be Our Guest. In addition, you’ll also hear Claude on the Jack Benny set Days of Our Lives. Happy birthday, Mr. Rains!