“From the far horizons of the unknown…”

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on Apr 24th 2017

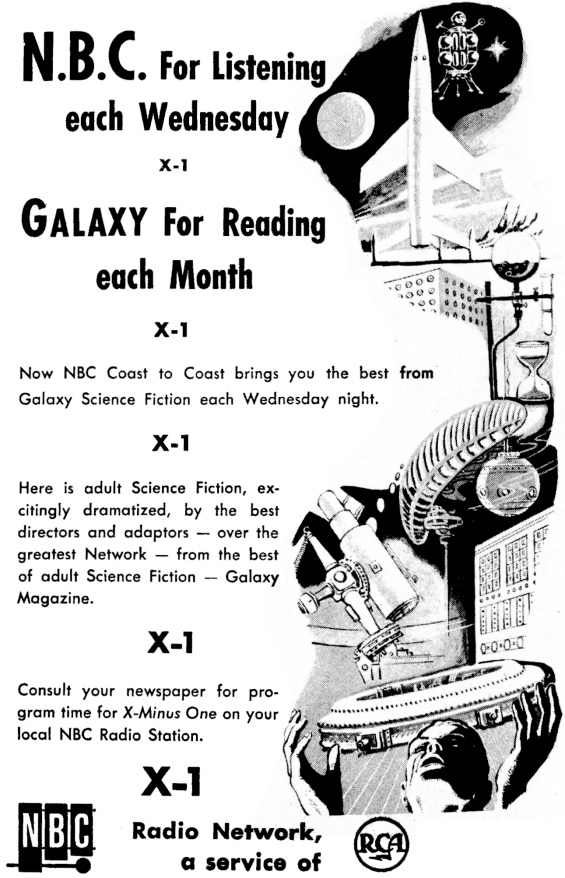

NBC Radio’s dramatic anthology Dimension X—which was inspired by a renewed interest in science-fiction following the release of Universal-International’s Destination Moon in 1950—was the most successful of the sci-fi radio dramas. (Others that premiered that same year include Mutual’s Two-Thousand Plus and CBS’ Beyond Tomorrow.) Its run on the airwaves was nevertheless brief, and the program bowed out on September 29, 1951. On this date in 1955, the National Broadcasting Company got a second bite of the apple when X-Minus One debuted, featuring its now-legendary signature opening: a rocket ship countdown leading to a “blast off” amid a chorus of voices blending in with the rocket roar.

“From the far horizons of the unknown come transcribed tales of new dimensions of time and space,” enthused announcer Fred Collins at the beginning of each broadcast. “These are stories of the future, adventures in which you’ll live in a million could-be years on a thousand maybe worlds. The National Broadcasting Company, in cooperation with Street and Smith—publishers of Astounding Science Fiction magazine—present… (Echo chamber effect) X (X…X…X…) Minus (Minus…minus…minus…) One (One…one…one…)…” The show’s association with Street and Smith was an important one. The earlier Dimension X took its stories from publications like Astounding Science Fiction and Galaxy, which were homes for legendary writers of the genre (including Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, and Robert Heinlein). As Dimension X’s producer, Van Woodward, explained: “We went the ‘adaptation route’ simply because that’s where the best stories are.”

The first fifteen broadcasts of X-Minus One—including the Ray Bradbury tales “Mars is Heaven” (05-08-55) and “The Veldt” (08-04-55)—were adapted from those originally heard on Dimension X. Bradbury was a rich source of inspiration for X-1 dramas, with first-rate versions of classics like “And the Moon Be Still as Bright,” “There Will Come Soft Rains,” “Marionettes, Inc.,” and “Zero Hour” tackled before the show’s microphones. “Nightfall,” “C-Chute,” and “Hostess” were adapted from stories penned by Isaac Asimov, while Robert Heinlein contributions included “Universe,” “The Green Hills of Earth,” and “Requiem.” (One of my favorite X-1 broadcasts is “The Roads Must Roll,” a Heinlein concoction in which the highway traffic of the future has become so congested that engineers have devised roads that move—similar to the automated walkways you find at airports.)

Other authors whose names will be familiar to science-fiction devotees also had their stories adapted on X-Minus One, including Robert Bloch (“Almost Human”), Philip K. Dick (“The Defenders,” “Colony”), Fritz Leiber (“A Pail of Air”), and Theodore Sturgeon (“Saucer of Loneliness,” “The Stars are the Styx”). The most important creative minds on that program, however, were NBC staff writers George Lefferts and Ernest Kinoy, who were responsible for the adaptation of these authors’ tales. The duo also contributed their own originals, notably Kinoy’s “The Martian Death March”—a fascinating allegory that mirrored the plight of Native Americans on reservations.

Every X-Minus One fan has their preferred episodes. Mine include “The Lifeboat Mutiny,” Robert Sheckley’s darkly humorous story of a HAL-like computer on a spaceship that’s programmed to protect its inhabitants…at any cost. (I also love Sheckley’s “Skulking Permit” (in which the government of a planet that has no concept of criminal behavior issues a license for two of its inhabitants to commit mayhem so as not to discourage corporate investors), and Tom Goodwin’s “Cold Equation” (the memorably chilling tale of a woman who stows away on her husband’s spaceship…oblivious to the fact that her extra weight could jeopardize the mission. But my all-time favorite remains Fredrik Pohl’s “Tunnel Under the World,” in which a man wakes up screaming day after day after day—the same day, in fact (shades of Groundhog Day!)—but only he seems to be aware of it. It’s the kind of drama that could only be effectively done on radio, “the theatre of the mind.”

The direction on X-Minus One was handled by veterans like Fred Weibe, Daniel Sutter, George Voutsas, and Kenneth MacGregor, while New York acting talents such as Mason Adams, Jack Grimes, Bob Hastings, John Gibson, and Bill Quinn numbered among the show’s unofficial stock company of performers. Despite its lack of sponsor, X-1 was a survivor at a time when radio was losing its audience to TV, and it continued to present fine audio drama until January 9, 1958. In the 1970s, when a brief interest in reviving radio drama was taking place, an attempt was made to rekindle the series with a January 27, 1973 audition episode called “The Iron Chancellor.” Beginning in June of that same year, X-1 was broadcast via repeat transcriptions…but its erratic scheduling (it aired once a month, sometimes on Saturdays…sometimes on Sundays) killed it in its cradle, with the experiment coming to an end on March 22, 1975.

“The most interesting dramatic of the 1955 season was produced by two genre series: Gunsmoke, a western, and this space opera.” That’s how old-time radio historian and author John Dunning described X-Minus One in his invaluable reference On the Air, and we at Radio Spirits are certain that you’ll agree that the program aired some of the finest radio drama ever broadcast. We are so sure of this that we invite you to check out the X-1 sets Archive Collection and Countdown, which feature such classic tales as my favorite, “Tunnel Under the World” (available on Archive Collection). “Drop Dead,” a broadcast that originally aired on August 22, 1957, is available on Radio Classics: Selected by Greg Bell, and you’ll find eight X-1 broadcasts (including “The Lifeboat Mutiny”!) on our compendium Science Fiction Radio: Atom Age Adventures. Happy anniversary to radio’s premier science-fiction program!