Review: Boston Blackie’s Rendezvous (1945)

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on Sep 27th 2014

As he and his sidekick The Runt (George E. Stone) settle in for the night, Horatio “Boston Blackie” Black (Chester Morris) gets an unexpected visit from his wealthy friend Arthur Manleder (Harry Hayden). Manleder needs Blackie’s help in the matter of his homicidal nephew James Cooke (Steve Cochran), who had been a guest at a mental institution until his recent crashout. As Arthur elaborates further on Jimmy’s past, the young Cooke is shown listening outside on a fire escape in Blackie’s apartment—and when Blackie calls it a night (after assuring Manleder he’ll look into the matter), Jimmy makes himself at home by entering Blackie’s bedroom. Jimmy’s story is that his uncle is purposely concocting a story questioning Jimmy’s sanity in a plot to keep him from receiving a large inheritance. Blackie tries to persuade Cooke to give himself up—and Jimmy’s reaction is to choke Mr. Black unconscious, then help himself to Blackie’s wardrobe.

Jimmy makes his way to a dance hall to meet a young woman named Sally Brown (Nina Foch), with whom he’s been corresponding during his incarceration. He’s informed that Sally isn’t working that evening, so he agrees to have a few dances with her roommate, Patricia Powers (Adele Roberts). He convinces Pat to go off with him so that the two of them can be alone. In the meantime, Blackie and The Runt follow clues left by Cooke and are hot on his trail; eventually they stumble onto the final resting place of Ms. Powers, who’s been strangled by Jimmy. Fans of the Boston Blackie movie franchise will not be surprised to learn, however, that our hero encounters Inspector John Farraday (Richard Lane) at the murder scene…and like so many times in the past, Farraday has fingered Blackie as the strangler.

The last part of the previous sentence goes a long way toward explaining why Boston Blackie’s Rendezvous (1945) is one of the weakest entries in Columbia’s successful movie series. Blackie is a reformed jewel thief and safecracker…but he’s not a murderer, and you would think that Farraday would realize this. Even an actor as solid as Dick Lane has difficulty making the audience believe that he’s convinced of his nemesis’ guilt. Rendezvous has other problems with its narrative as well: for example, in the opening scenes Jimmy explains to Blackie that his uncle Arthur has told people he’s insane in order to take his inheritance. We know from earlier Blackie vehicles that while Manleder is a man of considerable means, he’s also a gentle, kindly soul: a straight-shooter, firmly supportive of his friend and always in his camp. (Having a different actor—Harry Hayden—play the role shouldn’t make any difference.) The screenwriter of Rendezvous, Edward Dein (who later directed the 1955 cult classic Shack Out on 101), thereby makes no bones to those watching that Cooke is cuckoo-for-Cocoa-Puffs—when ambiguously suggesting Jimmy’s guilt of the strangulation murder might have been more effective.

Also telegraphing his punches is director Arthur Dreifuss, who held the reins on the previous entry in the Blackie series, Boston Blackie Booked on Suspicion (1945). Watch for the scene in Blackie’s apartment forty-five minutes in when Farraday gets on the phone to corroborate Blackie’s alibi—there’s a photo of B.B. prominently displayed on the desk, which catches Farraday’s eye (and produces an amusing grimace). There’s a reason for the photo, and all will be made clear at the film’s climax. (Farraday is also holding the phone’s receiver upside down, something that didn’t induce director Dreifuss to go for a retake.)

Actor Steve Cochran, who also figured prominently in Booked on Suspicion, plays the crazed Cooke in Rendezvous…and while there’s certainly no doubting his capability for onscreen violence and projecting a sense of menace, his attempt to portray Jimmy as a sensitive, poetic soul isn’t quite convincing. The leading lady of Rendezvous—who, for a nice change, doesn’t double-cross Blackie toward the movie’s conclusion—is Nina Foch, who was just earning her stripes as a Columbia starlet in programmers like The Return of the Vampire (1943), Cry of the Werewolf (1944) and the Crime Doctor series entry Shadows in the Night (1944). Her next film release after Rendezvous—apart from a bit role in Columbia’s A Thousand and One Nights (1945)—would be the B-picture classic My Name is Julia Ross (1945)…which led to such successes as The Dark Past (1948), The Undercover Man (1949) and Best Picture Oscar winner An American in Paris (1951). A few years later, Foch would score her sole Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress in 1954’s Executive Suite. (Queried in later years about Rendezvous, Nina couldn’t remember too many details…and I can’t say I blame her.)

Boston Blackie’s Rendezvous isn’t completely without merit: it features a scene-stealing performance from character great Iris Adrian, who played gum-chewing blonde wiseacres in nearly a million films (Lady of Burlesque, The Paleface) and also appeared on radio programs alongside Abbott and Costello and Jack Benny. Adrian is Martha, the ticket taker at the dance hall, and provides most of the film’s necessary lighter moments. You’ll also catch veteran Joe Devlin as a cab driver—Devlin, who could have been Jack Oakie’s twin brother, made a comfortable living in the movies portraying Italian dictator Benito Mussolini (he bore an uncanny resemblance to Il Duce) in The Devil With Hitler (1942), They Got Me Covered (1943), Natzy Nuisance (1943) and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944).

I got a chuckle out of seeing Tom Kennedy in a small role as a doorman outside the dance hall who gives Blackie information on Jimmy’s whereabouts (Kennedy was working steadily at Columbia at that time, appearing in a good many two-reel comedies with Shemp Howard), and Three Stooges nemesis Philip Van Zandt plays a psychiatrist who “analyzes” Blackie, thus allowing star Morris to do a few of his amateur magic tricks. Chet also trots out a blackface routine when he and Stone disguise themselves as cleaning women, which got me to wondering if Morris resorted to that bit of business more than Eddie Cantor, believed to be the onscreen record holder. (On top of this, one of my favorites, Clarence Muse, sadly plays “straight man” to the blacked-up Blackie and Runt.)

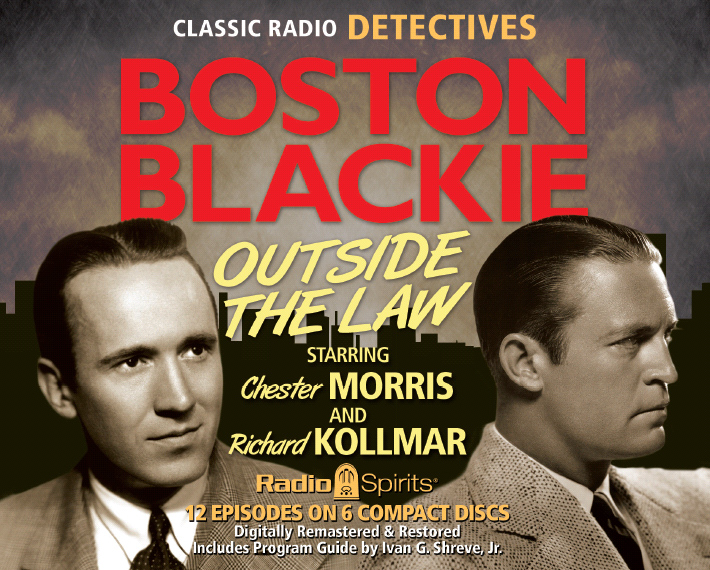

Next month: Blackie comes to the rescue of an old flame in A Close Call for Boston Blackie (1946)—one of only three movies in the series available on DVD (in a manufactured-on-demand disc from Sony Home Video), so you can watch it ahead of time and follow along in your workbooks. While I’m on the subject of availability, Radio Spirits’ fine collection of broadcasts from the Boston Blackie radio series—Outside the Law—is just what you need to enjoy the adventures of the former-thief-turned-crimefighter. Several of the shows on the set feature Chester Morris and Richard Lane in the roles they’d make famous in the movies. Grab a copy today…or two, in case you need one for a friend!