Review: Boston Blackie and the Law (1946)

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on Dec 22nd 2014

Previously on the Radio Spirits blog, I discussed Alias Boston Blackie (1942), the third entry in the popular Columbia Pictures movie franchise—it’s a holiday-themed picture, with the events taking place during Christmas Eve/Christmas Day and centering on Horatio “Boston Blackie” Black’s (Chester Morris) attempt to recapture an escaped convict who made a successful break as a result of our hero’s inviting a vaudeville troupe to entertain at a prison. Boston Blackie and the Law (1946), the twelfth Blackie outing, is a semi-remake of the earlier film; it simply does a gender switch (the prisoner on the lam is now a woman) and starts the plot on Thanksgiving.

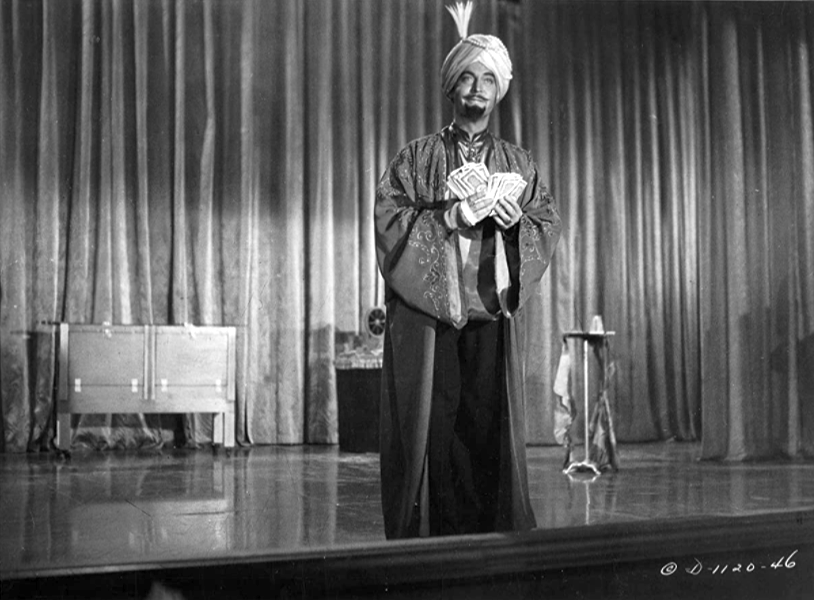

As part of a Thanksgiving Day party, Blackie is entertaining the inmates at a women’s prison…and when he announces his piece de resistance, a disappearing cabinet trick, the volunteer he solicits from the audience is one Dinah Moran (Constance Dowling)…who takes advantage of Blackie’s amateur prestidigitation by vanishing permanently. Naturally, Dinah’s disappearing act lands our hero in Dutch with the ever-suspicious Inspector Farraday (Richard Lane) and his sidekick Sergeant Matthews (Frank Sully). Unbeknownst to Blackie, Dinah was a former assistant to a magician named John Lampau (Warren Ashe); three years earlier, Ms. Moran was jailed along with her boss on suspicion of stealing $100,000 during a performance at a private party…and while Lampau was later cleared of any involvement, Dinah wound up taking the fall, serving a stint at the county’s bed-and-breakfast.

In tracking down Dinah, Blackie pays Lampau a visit at the theatre where he’s performing: he’s got a new name (Jani) and a new assistant named Irene (Trudy Marshall), whom he plans to marry. To recapture the fugitive Dinah, Blackie will not only have to press upon his amateur magic skills but his penchant for disguises (he impersonates Jani) as well.

In addition to his thespic duties on the silver screen, Chester Morris was an amateur magician—showing off his boyhood love of magic at a number of USO shows during the war years and working many of his tricks into the plots of the Boston Blackie films. No more is this evident than in Boston Blackie and the Law, which, despite Morris’ undeniable enjoyment at being able to show-off his craft, suffers a bit from a static script and some ham-handed attempts at humor. Off-screen, Morris got into a bit of trouble the following year when he revealed some of the “tricks of the trade” in an article for Popular Mechanics (“There’s Magic Up Your Sleeve”) that did not win him any fans in the magic community.

The problem with Law is that the paucity of suspects in the film makes it fairly easy for the viewer to suss out who’s responsible for committing two of the movie’s murders. In addition, while a healthy sense of humor has always been a hallmark of the Boston Blackie series, much of the comedy in Law comes off a bit forced. Case in point: When Blackie is brought into police headquarters to be interrogated as to what he knows of Dinah Moran’s prison break, we find that the magic cabinet he used in his performance happens to be in Farraday’s office. Announcing his intention to learn the disappearing trick by hook or crook, stumblebum Matthews examines the cabinet in vain …until Blackie volunteers to demonstrate how it’s done. A prolonged sequence of Blackie disappearing and reappearing in the box follows, with Matthews repeatedly assuring the apoplectic Farraday he did not let his nemesis escape. The repetition of this routine might have worked as an Abbott & Costello bit, but here it’s just tiresome.

This is not to say that Frank Sully’s Matthews doesn’t have his moments: later in Law, Farraday pieces together some of the elements of the mystery by glancing at a precinct report and he asks his dimwitted sergeant: “Matthews! Do you realize how important this is?!!” “Only because you’re excited, and that’s nothing new” is Matthews’ deadpanned response—Sully’s throwaway delivery of the line is a peach. The most ridiculous sequence in Law is a jailbreak by Blackie and his pal The Runt (George E. Stone), in which they outwit a turnkey (Syd Saylor) in a manner that suggests he might be a distant relative in the Matthews family. Director D. Ross Lederman may have earned the studio’s gratitude for cranking out their programmers on time and under budget…but his handling of this kind of comic material is truly leaden.

Constance Dowling plays the on-the-lam Dinah; Dowling’s films include Up in Arms (1944) and Black Angel (1946), and she would be reteamed with Chester Morris a year later in Blind Spot, a nifty little whodunit that should get exposure on TV more often. Audiences will probably be more familiar with the other female lead in Law: Trudy Marshall’s credits include The Sullivans (1944), The Purple Heart (1944), The Dolly Sisters (1946) and The Fuller Brush Man (1948). A gaggle of familiar character actors and Columbia contract players round out the cast, including Eddie Dunn and Selmer Jackson. And pay close attention to the woman who plays the librarian in the early portion of Law: it’s Maudie Prickett, who later played “Rosie” on TV’s Hazel(and Jack Benny’s sarcastic secretary in several episodes of his TV show).

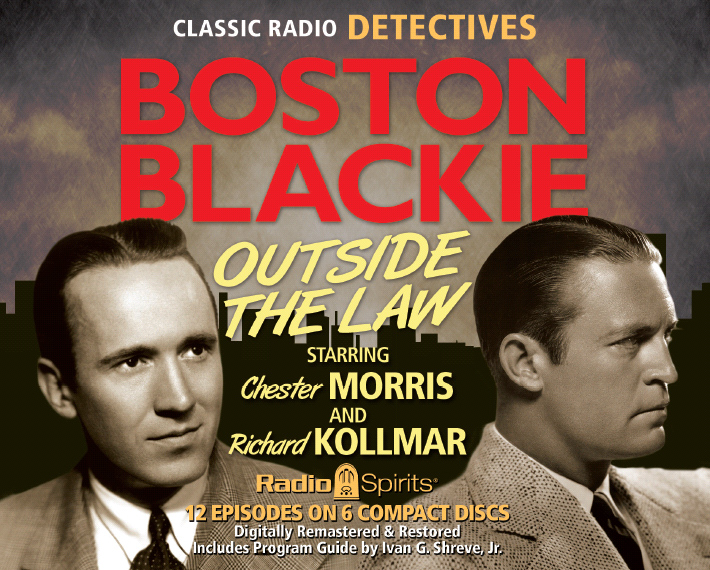

Next month, we’ll look at the penultimate Boston Blackie film—Trapped by Boston Blackie (1948)—in which a clever screenwriter decides that an ex-jewel thief is the perfect person to guard a precious pearl necklace. In the meantime, Radio Spirits reminds you that there’s plenty of byplay between Chester Morris’ Boston Blackie and Richard Lane’s Inspector Farraday in our CD set Outside the Law, which also features broadcasts from the team of Richard Kollmar (as Blackie) and Maurice Tarplin (Farraday). Check out a DVD collection of the boob tube adventures of our hero as well, starring Kent Taylor!