Review: After Midnight with Boston Blackie (1943)

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on May 20th 2014

Jewel thief “Diamond” Ed Barnaby (Walter Baldwin) has just been paroled from prison, and his loving daughter Betty (Ann Savage) is anxious to make a new life with him…but “Diamond” Ed has a few loose ends to tie up. His last job netted him a nice little haul of diamonds that he feels rightly belong to Betty—but racketeer Joe Herschel (Cy Kendall) begs to differ. Herschel assigns a couple of his goons (Al Hill, George McKay) to retrieve the gems from Ed, who’s stashed his nest egg in a safety deposit box for safe keeping.

Returning by train from a trip to Chicago, Boston Blackie (Chester Morris) and his loyal sidekick The Runt (George E. Stone) are handed a telegram from Betty…who needs Blackie’s help in locating her father after he fails to show up for an appointment. Actually, it’s a second-hand telegram—Blackie’s nemesis, Inspector Farraday (Richard Lane), and his dimwitted partner Sergeant Matthews (Walter Sande), originally intercepted the message in an effort to keep up-to-date on Blackie’s activities. Blackie and The Runt do a little investigating once they’re off the train and learn of Barnaby’s safety deposit box. Unfortunately for them, Farraday has intercepted a phone call from Ed telling him that “two men are headed for the box” shortly before he’s killed by an unknown assailant. When he catches Blackie and Runt breaking into the box, Farraday naturally puts two and two together…though with his track record, it rarely adds up to four.

Howard J. Green’s screenplay for After Midnight with Boston Blackie (1943)—based on a story by Aubrey Wisberg—continued the success of Columbia Pictures’ B-movie series based on Jack Boyle’s reformed safecracker and jewel thief from novels and pulp magazines. Lew Landers returns to direct his second film in the Blackie series; he held the reins earlier on Alias Boston Blackie (1942) and would direct one more B.B. vehicle with A Close Call for Boston Blackie in 1946. (On a brief side note, I happened to catch an earlier collaboration with Landers and star Morris the other day: the 1937 programmer Flight from Glory, which also features Richard Lane in the cast. It’s sort of a proto-Only Angels Have Wings, in which Morris, Lane and a young Van Heflin play disgraced pilots flying dangerous cargo missions in the Andes.) The producer of After Midnight, Sam White, had a brother working for Columbia that some of you might know: Jules White, the head of the studio’s shorts department who cranked out two-reel comedies with the Three Stooges, Andy Clyde and so many others.

After Midnight with Boston Blackie is a slight drop in quality from the previous Blackie films. It’s not that it isn’t entertaining; it’s just that the plot (a sort of “Button, Button, Who’s Got the Button?”) lacks the cohesiveness of earlier entries. Screenwriter Green worked in a sequence in which Blackie and Company have to operate during a blackout (it’s a wartime thing) that was topical for the time but might not completely gel for modern audiences—though I did get a kick out of how Blackie, in a tight spot with Betty, signals he needs assistance by knocking out the letters in a sign that reads “HOTEL PARK” to form “HELP.” (I bet they got that idea from a gag in Abbott & Costello’s Who Done It?) There’s also a bit in which Blackie dons a bit of blackface (he’s disguised himself as a bull fiddle player, amusingly played by comedian Dudley Dickerson) that might make those same audiences wince in these more enlightened times.

After Midnight does feature a funny subplot involving The Runt; he’s engaged to be married to a showgirl named Dixie Rose Blossom (Jan Buckingham), and Blackie’s pal Arthur Manleder (Lloyd Corrigan reprises his series role) is hosting the nuptials at his apartment, complete with justice of the peace (played by character fave Dick Elliott). The investigation of Diamond Ed’s murder keeps putting the event on hold, and at the end of the film, The Runt is ready to walk down the aisle with his fiancée when Farraday and Matthews show up unannounced…to arrest Dixie Rose for bigamy! A relieved Runt cracks to Manleder: “That’s the first time Farraday ever did me a good turn!”

Character veteran Cy Kendall makes his third appearance in this Blackie vehicle—but not in his usual persona as Jumbo Madigan, Blackie’s underworld contact (instead, Kendall is ruthless nightclub owner Joe Herschel). Kendall would play Jumbo one more time in the next entry in the series, The Chance of a Lifetime (1943), and then Joseph Crehan would tackle the part in two more Blackie films. After Midnight features quite a few familiar faces—Walter Baldwin, Don Barclay, Eddy Chandler, Heinie Conklin, John Harmon, Eddie Kane—but the most familiar is no doubt that belonging to Ann Savage, who plays the female lead. Before Ann became a cult favorite for her one-of-a-kind performance as the deadly femme fatale opposite Tom Neal in 1945’s Detour, she was a contract player at Columbia, appearing in such films as Footlight Glamour (1943), One Dangerous Night (1943) and Passport to Suez (1943). (These last two features were part of Columbia’s popular Lone Wolf franchise with Warren William and Eric Blore.)

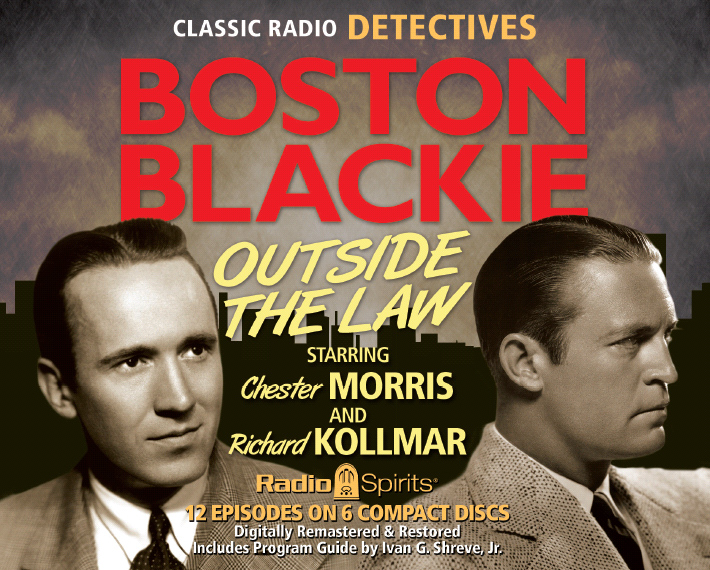

Next month on the blog: Blackie’s idea to have convicts work as labor for the war effort goes south thanks to one prisoner who’s out to collect the proceeds from a robbery…which finds him at odds with the men who were in on the job, since they want a piece of the pie as well. It’s The Chance of a Lifetime (1943), the motion picture that would serve as the feature film debut for a director who would make his fortune with a series of popular “gimmicky” horror movies in the 1950s/1960s as well as produce the terror classic Rosemary’s Baby (1968). And don’t forget to check out star Chester Morris in the Radio Spirits CD release Boston Blackie: Outside the Law!