“Heavenly days!”

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on Apr 16th 2015

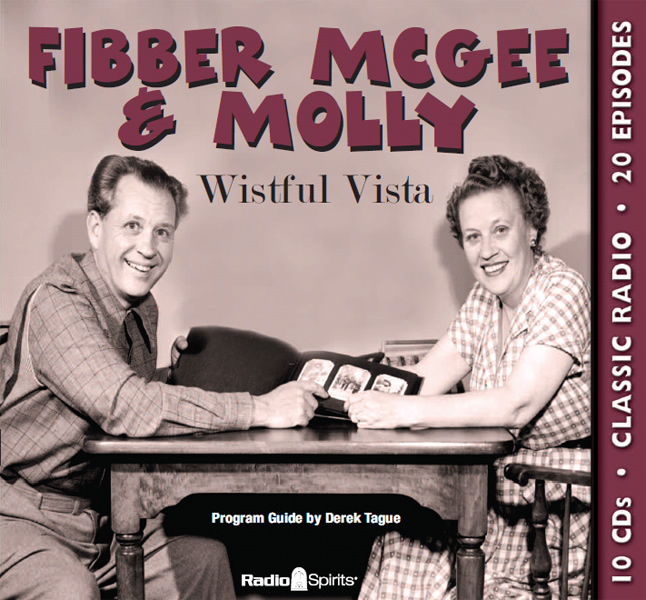

The day that writer Don Quinn crossed paths with Jim Jordan at WENR in Chicago would prove to be a most fortuitous one for both men…and for Jim’s wife Marian as well. The Jordans arrived on radio by way of vaudeville. Although radio didn’t pay nearly as well as stage work at the time, both Jim and Marian liked the ease and comfort of not having to undergo the grueling travel required by performers of the time. Quinn would sign on to become the author of Smackout, a weekday quarter-hour starring Jim and Marian that began on Chicago’s WMAQ in 1931 before moving to the national NBC lineup. One of Smackout’s fans was Henrietta Johnson Louis, the wife of ad executive John J. Louis, who convinced her hubby that the Jordans would be perfect for a new show Johnson’s Wax was looking to sponsor in 1935. That show premiered on this date as The Johnson’s Wax Program…but we know it as Fibber McGee & Molly.

In their early broadcast days, the characters of Fibber & Molly McGee were on what we would refer to nowadays as a “road trip.” The couple traveled around in a dilapidated old jalopy, ostensibly to promote a Johnson’s product entitled Car-Nu. But once summer was over, the company wanted to switch to hawking Johnson’s Glo-Coat, and so with the purchase of a winning raffle ticket, the McGees found themselves the proud owners of a house at 79 Wistful Vista…soon to become one of radio’s most popular addresses.

It was probably a good thing that the McGees owned their home…because Mr. McGee wasn’t much of a provider in the traditional husbandly sense. Fibber wasn’t really lazy, just unmotivated; many of the show’s plots would find him employed in some capacity…and by the end of the broadcast he’d be in search of work again. McGee was a good man, it’s just that he earned his nickname “Fibber” for a reason—he had a propensity for stretching the truth and liked to while away the hours telling tall tales to anyone unfortunate enough to be within earshot. His wife Molly loved him despite his serial exaggerations, and her warm, loving demeanor was just the remedy needed to the take the wind out of her blustery spouse’s sails. Her voice was reassuring and comfy, always greeting newcomers to the house with a “How do you do, I’m sure.” (Marian Jordan was sorely missed when she was forced to take a leave of absence from the program from September 1937 to April 1939, so much so that the show was briefly renamed Fibber McGee and Company.)

The ratings for Fibber McGee & Molly were anemic at first; they had the misfortune of being up against the popular Lux Radio Theatre on Monday nights. But a switch to Tuesday nights helped the listenership immensely, and soon loyal audiences couldn’t get enough of Fibber and Molly’s misadventures. The show also developed many memorable supporting characters: Bill Thompson, who began appearing on the show in 1936, played Greek cafeteria owner Nick DePopolous (who got laughs via malapropisms and mispronunciations) and shady con man Horatio K. Boomer (whose voice was a dead ringer for W.C. Fields). Several years later, Thompson would introduce two of the program’s most enduring personages: The Old Timer, a half-deaf old codger who could out-tall-tale Fibber any day of the week (“That’s pretty good, Johnny—but that ain’t the way I heared it!”), and Wallace Wimple, a cheerful milquetoast who paid Fibber and Molly frequent visits to escape the wrath of his formidable wife Sweetyface.

Gale Gordon also became a regular on the program, playing Charles LaTrivia, Wistful Vista’s mayor—whose visits with the McGees usually left him in a frustrated state of tongue-tiedness. (Gordon introduced a character in the show’s later years that was always one of my favorites: F. Ogden “Foggy” Williams, the town weatherman, who always announced his exit with “Good day…probably!”) Actress Isabel Randolph was the snooty Abigail Uppington, who never tired of looking down at Fibber and Molly’s lowly social status. (Mrs. Uppington was later replaced by the equally condescending Millicent Carstairs, played by Bea Benaderet, and Elvia Allman emoted as Mrs. Albert Clemmer after Bea’s departure.) Other actors who appeared on The Johnson’s Wax Program on a regular basis include Cliff Arquette, Hugh Studebaker, Richard LeGrand (as Ole, the Elks’ janitor) and Ransom Sherman. Marian Jordan doubled as other characters when the need arose: her best remembered supporting role was “Teeny,” the little neighbor girl who often drove Fibber to distraction.

Actor-singer Harold Peary played a variety of characters on the show before he was able to convince Don Quinn to write him a meatier part: that of Fibber’s pompous next-door neighbor, Throckmorton P. Gildersleeve. The only man in Wistful Vista windy enough to match McGee’s bluff, Gildersleeve and Fibber were purportedly best friends…though the two of them engaged in an awful lot of quarreling and traded a good many insults. Peary’s Gildersleeve would later become so popular that NBC agreed to spin the character off in a situation comedy entitled The Great Gildersleeve, which premiered in August of 1941.

Then, with America’s entry into World War II at the end of 1941, The Johnson’s Wax Program became one of the benchmarks by which patriotism on the radio homefront was measured. The McGees beseeched their listening audience to do all they could for the war effort (like buying war bonds and planting victory gardens), and many of their broadcasts were built around this theme. (For example: cognizant of gas rationing, Fibber and Molly often depended on four-legged transportation—their horse Lillian.) The war kept two of their cast members occupied, Thompson and Gordon, so the show was forced to create new characters to make up for the deficit.

Arthur Q. Bryan was soon brought aboard as Dr. George Gamble, a corpulent physician who replaced Gildersleeve as Fibber’s verbal punching bag…though the erudite medico often got the better of his nemesis in their oral entanglements. Shirley Mitchell played man-crazy Alice Darling, a war worker who boarded with the McGees. The character with the most influential impact was an African-American maid named Beulah that Fibber and Molly hired in 1944. Unbeknownst to home listeners, Beulah was played by a white actor named Marlin Hurt, who got shrieks of laughter from the studio audience whenever he would spin around (he spent the time until his entrance with his back to the audience) and holler his first line. The character of Beulah later migrated to a spin-off as well, in CBS’ The Marlin Hurt and Beulah Show in 1945.

Fibber McGee & Molly continued to be popular with radio listeners once the war ended, and fans tuned in religiously each week to hear their favorite catchphrases (“Tain’t funny, McGee!”, “Dadrat the dadratted…”). The most popular running gag on the show was introduced in 1940: the McGees had a closet at 79 Wistful Vista that had become home to numerous piles of junk and bric-a-brac over the years. And because the contents of the closet had been organized with the kind of discipline you’d expect of a man nicknamed “Fibber,” when some unlucky individual (usually McGee) opened the closet…an avalanche of odds and ends came spilling out (courtesy of the show’s preeminent sound effects man). “Gotta straighten out that closet one of these days,” McGee would wind up muttering.

Jim and Marian Jordan were a rarity in radio: they were practically alone among the medium’s top comedy acts who had no interest in transitioning to television. They filmed a pilot at Johnson Wax’s request, but having fulfilled that obligation, the couple decided that newfangled boob tube had nothing to offer them. So they amicably split with their longtime sponsor at the end of the 1949-50 season, and for the next two years Pet Milk paid their bills, with Reynolds Aluminum writing the checks for the final season their half-hour show was on the air. The thirty-minute adventures of the McGees ended on June 30, 1953, and in October of that same year Jim and Marian’s show became a five-day-a-week quarter-hour that was heard until March 23, 1956. The couple also performed in Fibber and Molly skits on NBC’s Monitor between 1957 and 1959.

The traditional gift for eightieth wedding anniversaries is oak…which would be kind of appropriate in the case of Fibber and Molly; one of the subtlest running gags on their program was that the address for any home, business or government building was always located at 14th and Oak. We at Radio Spirits, however, suggest a more suitable anniversary gift: Fibber McGee & Molly collections Whoppers, That Ain’t the Way I Heared It, and the crème de la crème of their wartime broadcasts available on Wistful Vista. For Yuletide McGee mirth, we recommend checking out Christmas Radio Classics, Radio Christmas Celebrations and The Voices of Christmas Past; Fibber and Molly also figure prominently in our Road Trip: Humorous Travel Tales collection. If you’re curious about the origin of Fibber’s famous closet, our Burns and Allen: Gracie for President can take you back to when it all began. And keep your eyes peeled for the brand spanking new Fibber McGee & Molly: For Goodness Sakes collection, which will be available for purchase next week! Happy anniversary, Fibber and Molly!