Happy Birthday, James Cagney!

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on Jul 17th 2020

When we think of the man that Orson Welles once described as “maybe the greatest actor who ever appeared in front of a camera” it’s usually as the motion picture industry’s consummate tough guy, with memorable appearances in such iconic films as Angels with Dirty Faces (1938) and White Heat (1949). James Cagney, however, was a performer of incredible versatility: he sang and danced in Footlight Parade (1933), spouted Shakespeare in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), and won the respect and admiration of his movie peers by grabbing an Oscar trophy portraying showman George M. Cohan in Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942). The first actor selected to receive the American Film Institute’s Lifetime Achievement Award (in 1974), James Francis Cagney, Jr. arrived on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in NYC on this date in 1899—no doubt asking the doctor who delivered him: “Whaddya hear? Whaddya say?”

The son of Carolyn and James, Sr. (a bartender and amateur boxer), James Cagney was the second of seven Cagney children…although two of them died within months of their births. Jimmy lived a hardscrabble life of poverty, and his poor health in childhood was often attributed to his family’s financial difficulties. Cagney graduated from NYC’s Stuyvesant High School and enrolled in Columbia College with the intention of getting an art degree. He dropped out after one semester, returning home to help the family after his father succumbed to the 1918 flu pandemic.

James Cagney worked a variety of jobs at this period of his life, including copy boy (for the New York Sun) and bellhop. He developed a love of tap dancing in his childhood while participating in amateur theatrics. A woman named Florence James can claim credit for first putting Jimmy on stage, but it was while working at a department store in 1919 that a colleague gave him a heads-up about an upcoming production entitled Every Sailor. Cagney didn’t think he had a chance of getting hired, but the producers were impressed with his audition enough to give him a job…as a dancer in the female chorus line. Jimmy was grateful for the $35-a-week salary, but his mother influenced his decision to leave after two months, wanting him to get an education. His retirement from performing didn’t last long; Cagney later became a chorus boy in the Broadway revue Pitter Patter, pulling down $55 a week ($40 of which went to Mama Cagney).

Thus began James Cagney’s 10-year-association with vaudeville and Broadway, working his way up from the chorus to male leads (including his first dramatic role in 1925’s Outside Looking In—he beat out a pre-Ethel and Albert Alan Bunce for the part because his hair was redder). Along the way, he married dancer Frances Willard “Billie” Vernon in 1922, who remained Mrs. Cagney until Jimmy’s death. Cagney’s Broadway triumphs included Women Go On Forever (1926) and Grand Street Follies (1928/1929); Jimmy’s turn in Penny Arcade (1930) won critical acclaim even if critics didn’t care for the material. Al Jolson bought the rights to Arcade for $20,000 and sold them to Warner Brothers under the stipulation that the studio keep Jimmy and female lead Joan Blondell (who had acted alongside Cagney in a previous play, Maggie the Magnificent [1929]). Arcade was retitled Sinners’ Holiday (1930) for the screen and, while Warners had some initial doubts about Jimmy, it wasn’t long before they realized they had a hot property in their stable.

In Holiday, James Cagney played a tough guy who becomes a killer and he continued in that same vein in a follow-up film, The Doorway to Hell (1930). The Public Enemy (1931) would be Cagney’s true Hollywood breakthrough. Even today, Enemy crackles with energy in its iconic sequences of Jimmy shoving a grapefruit in Mae Clarke’s face and Cagney’s memorable demise at the end. A role in Smart Money (1931), a gangster flick which paired him with fellow studio menace Edward G. Robinson (in their sole feature film teaming), only further cemented Cagney’s rise to stardom. James Cagney was one of the most unconventional of movie stars—he didn’t possess leading man looks (he was short and rather ordinary looking), but his vitality and two-fisted toughness made him ideal for the studio’s output of social dramas and gangster sagas.

Having a star of Jimmy Cagney’s talent on the payroll, Warner Bros. missed few opportunities to showcase him at every opportunity. Jimmy made a lot of movies for the studio during the early 1930s, many of them he didn’t want to participate in…which gave him a reputation for being “difficult.” To express his dissatisfaction, the actor would resort to such tactics as adopting an unattractive haircut (1934’s Jimmy the Gent) or sporting a risible pencil-thin mustache (1934’s He Was Her Man). Cagney’s dissatisfaction with Warners would lead to his suing the studio for breach of contract in 1935. While awaiting the outcome of that case, Jimmy accepted an offer from independent studio Grand National to make motion pictures—two of which were released (a third didn’t get made because the studio ran out of money), Great Guy (1936) and Something to Sing About (1937).

The courts ultimately ruled in James Cagney’s favor, and the actor returned to Warner Brothers in 1938 to make several movies beloved by classic film fans today: Dirty Faces, The Roaring Twenties (1939), Each Dawn I Die (1939), and the Oscar-winning Yankee Doodle Dandy. He and his brother William decided to become independent filmmakers through United Artists in 1942, and though he released such features as Johnny Come Lately (1943) and Blood on the Moon (1945), Jimmy would return to Warners in 1949 after a third “Cagney Productions” film, The Time of Your Life (1948), really gave the company a soaking. Part of Cagney’s agreement to return to Warner Brothers was that they would clean up the financial mess left by Time; in return, Jimmy gave the studio a substantial hit by once again returning to his gangster roots with White Heat.

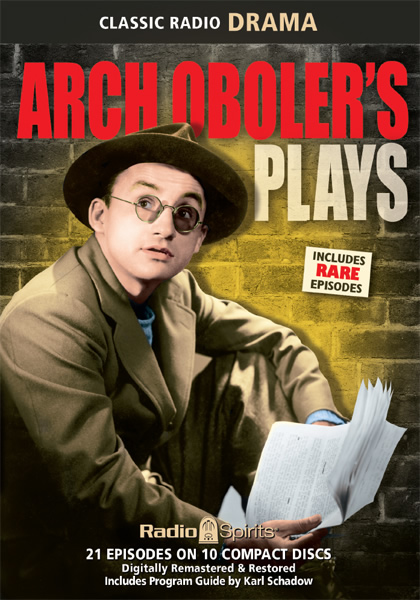

By the 1950s, James Cagney’s star luster had started to dim a bit, though he continued to make critically-acclaimed films like Mister Roberts (1955), Love Me or Leave Me (1955; playing Marty “The Gimp” Snyder opposite Doris Day’s Ruth Etting), and Man of a Thousand Faces (1957; as silent film star Lon Chaney). He even dabbled in directing—a remake of 1942’s This Gun for Hire entitled Short Cut to Hell (1957). Even with an uproarious performance in the Billy Wilder-directed One, Two, Three (1961), Cagney was ready to retire and live the life of a gentleman farmer on his spread in upstate New York. During his movie heyday, Jimmy often reprised his motion picture roles in radio venues like The Cavalcade of America, Family Theatre, The Gulf/Lady Esther/Camel Screen Guild Theatre, The Lux Radio Theatre, and The NBC Star Playhouse. Cagney had two very memorable radio showcases on Arch Oboler’s Plays (an adaptation of Dalton Trumbo’s anti-war novel. Johnny Got His Gun) and Suspense (a good little installment entitled “No Escape”).

It wasn’t until 1981 that James Cagney was coaxed back into the movies: partly because his doctors recommended physical activity for his ailments (including diabetes) and partly to work with his old chum Pat O’Brien once again. (The two actors made a total of nine films together including Ceiling Zero [1935] and Torrid Zone [1940].) As New York Police Commander Rhinelander Waldo in an adaptation of E.L. Doctorow’s novel Ragtime, Jimmy demonstrated he was still the consummate pro (film critics ran out of superlatives to describe how good it was to have him back). Sadly, it was Pat O’Brien’s cinematic swan song. Cagney would only make one more movie (with Art Carney), the 1984 TV-film Terrible Joe Moran, before his passing in 1986 at the age of 86.

I mentioned earlier an appearance James Cagney made on Arch Oboler’s Plays—a March 9, 1940 performance of “Johnny Got His Gun,” with Jimmy as a war veteran who’s blind, deaf and mute..and has no arms or legs. It’s powerful radio, and you’ll find it on Radio Spirits’ Arch Oboler’s Plays collection. Today’s birthday boy is also one of the many subjects featured on our documentary DVD Hollywood’s Greatest Screen Legends and the 1975 cinematic documentary mosaic Brother Can You Spare a Dime? Happy birthday, Jimmy!