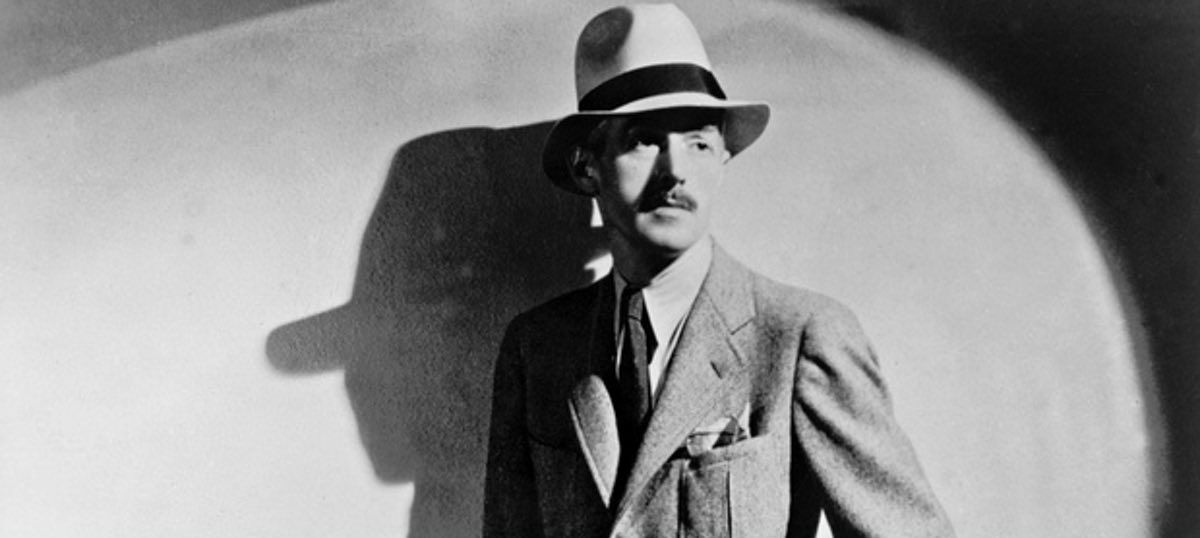

Happy Birthday, Dashiell Hammett!

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on May 27th 2017

“I’ve been as bad an influence on American literature as anyone I can think of.” So declared the man born Samuel Dashiell Hammett on this date in 1894, a confession he made to his daughter Josephine in a display of cynicism that would be most appropriate of his famous literary creation, shamus Sam Spade. Hammett was selling himself short, however. His career as a novelist and writer of short stories would also have a profound effect on movies and television…and for old-time radio fans, without a little “Dash” there would be no adventures with either the Thin Man or the Fat Man.

Born in St. Mary’s County, Maryland, young Dashiell Hammett left school at the age of 13 and occupied himself with a series of menial jobs, including stints as a freight clerk, railroad laborer, and stevedore. He became a detective with the famous Pinkerton Agency (“We never sleep”) in 1915 and would later capitalize on that employment by integrating his experiences into his hard-boiled detective fiction. His on-again, off-again time spent with the agency lasted nearly a decade. He enlisted in the Army during World War I and became a sergeant in the Motor Ambulance Corp…and contracted tuberculosis during his hitch. The condition would plague him for the remainder of his life, yet it was during his stay as a patient at Cushman Hospital in Tacoma, Washington that he was cared for by nurse Josephine Dolan. The two of them would wed in 1921.

Most biographies of Hammett state that he left Pinkerton due to his tubercular condition (Dash surmised that it would be a handicap as a detective) but tend to gloss over the fact that the decision to depart was hastened by an incident that occurred in 1917—when labor organizer Frank H. Little was lynched in Butte, Montana for his union and anti-war activities. Hammett was employed by Pinkerton as a strike breaker, and allegedly was offered $5,000 to “assassinate” Little (a claim the author made to his longtime companion Lillian Hellman). Dash refused, but the episode would haunt him for the rest of his life; it is speculated that the Little murder influenced Hammett’s later political leanings…and it became the basis for the plot of Red Harvest, the author’s first novel in 1929.

After leaving the Pinkertons, Dashiell Hammett decided to try his hand at writing. His first story, “The Parthian Shot,” appeared in the pages of The Smart Set in 1922…but his kind of writing, which would soon be described as “hard-boiled” detective fiction, seemed a little out-of-place in such a “society” publication. “The Road Home,” his second effort, would find a home at the pulp magazine Black Mask, and his third contribution for the magazine (published in 1923), “Arson Plus,” introduced the gumshoe known as “The Continental Op” (the detective had no name, but worked for the Continental Detective Agency). Hammett drew on his former experiences as a Pinkerton dick, basing many of the characters in his stories on people he knew and setting many of the tales against the backdrop of San Francisco, his base of operations during his time with the agency. (In his early stories, Dash adopted “Peter Collinson” as his pen name before going with “Dashiell Hammett” for his byline.)

As previously noted, Dashiell Hammett’s debut novel, Red Harvest, hit bookstores in 1929 and was quickly followed with a second effort, The Dain Curse. (Both novels are narrated by “The Continental Op,” and both had been previously published in Black Mask in serialized installments.) Red Harvest was never officially adapted for the silver screen, but its plot would later be borrowed for the Akira Kurosawa-directed Yojimbo in 1961 (and by Sergio Leone when he used Yojimbo as a template for A Fistful of Dollars in 1964). In addition, elements would later turn up in the Coen Brothers’ Miller’s Crossing (1990). His third novel (also previously serialized in Black Mask in 1929) was the legendary The Maltese Falcon—which inspired three movie versions in 1931, 1936 (as Satan Met a Lady), and 1941.

Dashiell Hammett’s fourth novel, The Glass Key, would also receive the motion picture treatment with films released in 1935 and 1942. By this point in his writing career, Hammett was looking for opportunities to write for the movies—his marriage to Josephine was deteriorating (doctors advised Jo and their two daughters to live in a separate residence from Dash due to his tuberculosis). To compensate, he began a romance with a 24-year-old aspiring playwright named Lillian Hellman that would last for the rest of his life. (Though he and Hellman would eventually divorce their spouses, the two of them never married.) The affair with Hellman would inspire his last published novel, The Thin Man—Hammett asserted that the tipsy society couple known as Nick and Nora Charles was based on Lillian and himself. Published in 1934, the book would be adapted in motion picture form that same year by MGM, who would produce five additional movies featuring the Charleses (the last released in 1947).

Dashiell Hammett’s career as a professional writer eventually petered out with the publication of The Thin Man; he only wrote a few short stories after that, and his contribution to the comic strip Secret Agent X-9 (drawn by Alex Raymond) lasted only a year. Hammett produced some work for the movies (he receives story credit for City Streets [1931] and Woman in the Dark [1934]), but he mostly served as a sounding board and editor for Hellman. (Some have even suggested that he was Lillian’s co-writer; he’s credited with the screenplay for Watch on the Rhine [1943], adapted from her stage play.) Dash’s poor health played a large role in his inactivity at this point in his career, yet the success of the movies based on his creations (Sam Spade, Nick and Nora) helped him keep body and soul together.

Hammett’s characters would achieve much fame in the aural medium as well. A program (produced by Inner Sanctum’s Himan Brown, who learned to his astonishment that no one had bothered to snap up the radio rights to Nick and Nora) entitled The Adventures of the Thin Man premiered in July of 1941 and would be heard on NBC, CBS, and ABC until September of 1950. Suspense producer William Spier introduced tales of “the greatest private detective of them all” with The Adventures of Sam Spade in July of 1946, a popular crime drama that aired until 1951. Completing the Hammett hat trick was The Fat Man, a series whose protagonist some have speculated was based on “The Continental Op”; that popular show was heard on ABC from 1946 to 1951. Hammett’s participation in these programs continues to be a subject of debate among scholars today, but I’ve always speculated that it was minimal at best. “My sole duty in regard to these programs is to look in the mail for a check once a week,” he declared in 1949. “I don’t even listen to them. If I did, I’d complain about how they were being handled, and then I’d fall into the trap of being asked to come down and help.”

Dashiell Hammett was passionately committed to leftist political causes…and that spelled trouble after WW2, when the U.S. started looking for new villains after defeating the Nazis. Dash was an ardent supporter of New York’s Civil Rights Congress, and when four of that organization’s members jumped bail in 1951 rather than surrender to federal agents (they had been convicted under the Smith Act “for criminal conspiracy to teach and advocate the overthrow of the United States government by force and violence”) Dash was summoned to appear before the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York to testify as to the whereabouts of the fugitives. Echoing the same moral code as many of the characters in his works, Hammett refused to divulge any information and was found in contempt of court (he served his six-month sentence in a West Virginia penitentiary, cleaning toilets). Hammett would also run afoul of the House Un-American Activities Committee (he had joined the Communist Party in 1937) and the IRS also decided to stick a shiv in, coming after him for $100,000 in back taxes and garnishing any future earnings. His alcoholism and tuberculosis continued to worsen, and he was forced into seclusion at a cottage in Katonah, NY where he suffered a heart attack in 1955…and then passed away six years later.

Dashiell Hammett’s contemporary Raymond Chandler—the creator of Philip Marlowe—remarked in his seminal essay “The Simple Art of Murder”: “Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse…he put these people down on paper as they were, and he made them talk and think in the language they customarily used for these purposes.” There’s a reason why Hammett is considered “the dean” of hard-boiled detective fiction, and that bad influence referenced in the first paragraph of this post was certainly evident in Radio’s Golden Age. Skeptical? Well, Radio Spirits invites you to check out Smithsonian Legendary Performers: Dashiell Hammett—a six-CD collection featuring radio adaptations of such famous Hammett works as The Maltese Falcon and The Glass Key (from the likes of The Lux Radio Theatre and The Screen Guild Players) and episodes of The Fat Man, The Adventures of the Thin Man, and The Adventures of Sam Spade. (You’ll find additional “capers” from Mr. Spade on our collection Lawless as well.) Our birthday celebrant also rates a mention in The Best of Blood ‘n’ Thunder, Volume 2, a book that compiles articles from the publications dedicated to pulp fiction and edited by my good friend Ed Hulse—a perfect gift for fans of adventure and mystery!