Happy Birthday, Cary Grant!

Posted by Ivan G. Shreve, Jr. on Jan 18th 2015

For those of you disappointed in the Academy Award nominations announced this past Thursday, here’s a little something to chew on: one of the most beloved motion picture stars of all time (he was named by the American Film Institute as the second Greatest Male Star of all Time, right behind Humphrey Bogart)…never won a competitive Oscar. The man born Archibald Alexander Leach in Bristol, England on this date in 1904 did receive two nominations—both for films considerably out of the wheelhouse of light/screwball comedy genre for which he was best remembered. Cary Grant grabbed Best Actor nods in 1942 (for 1941’s Penny Serenade) and 1945 (1944’s None But the Lonely Heart) but was nudged out on both occasions…he’d have to wait until a few years after he ceased moviemaking to earn the recognition of his peers with an honorary trophy.

When we think of Cary Grant, we think of an actor who was the epitome of urbane sophistication; a practiced farceur who did splendid work in any number of film comedies: Topper (1937), The Awful Truth (1937), Bringing Up Baby (1938), Holiday (1938), His Girl Friday (1940), My Favorite Wife (1940), The Philadelphia Story (1940)…well, this list could probably continue until the end of time. Yet Grant excelled in dramatic roles as well (always leavened with a light touch), as the likes of Gunga Din (1939), Only Angels Have Wings (1939), Mr. Lucky (1943), and Destination Tokyo (1944) will readily attest. Grant would become one of director Alfred Hitchcock’s favorite leading men: Cary first worked with the Master of Suspense in 1941’s Suspicion (Hitch had wanted to make Cary the villain but was forced to abandon that plan at the request of the studio), and later co-starred with Ingrid Bergman in what some have called one of Hitchcock’s finest films from the 1940s: Notorious (1946).

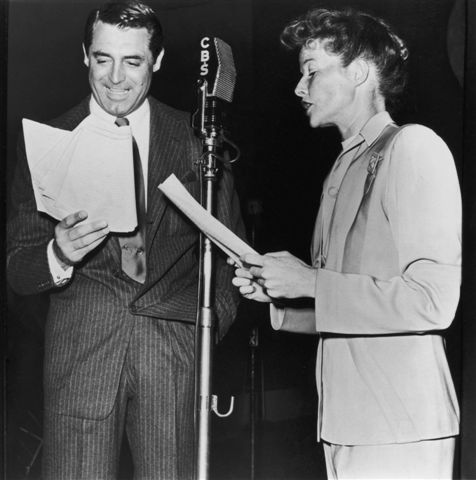

Since there have been reams of paper written about Grant’s motion picture legacy—and acres of bandwidth colonized expounding on his contributions to film—let’s explore Cary’s contributions to the aural medium. Like most of the top movie celebrities at that time, he was made most welcome on CBS’ The Lux Radio Theatre, where he appeared on multiple occasions reprising the roles he popularized onscreen in films like Madame Butterfly (1932), The Awful Truth and Only Angels Have Wings. (Grant was also occasionally called upon to act in productions of movies he did not star in; he appeared alongside frequent movie co-star Irene Dunne in a June 13, 1938 Lux broadcast of Dunne’s Theodora Goes Wild, in which her original onscreen leading man was Melvyn Douglas.) Cary also emoted on such shows as The Silver Theatre, The Screen Guild Theatre, Theatre of Romance, The Cavalcade of America, Academy Award Theatre and Command Performance.

One of Cary’s earliest and most interesting radio gigs was a short-lived program entitled The Circle, which premiered over NBC on January 15, 1939. An hour-long “talk show” (that sounded spontaneous but was tightly scripted), Circle not only brought Grant to the microphone but also Ronald Colman, Carole Lombard, and Groucho & Chico Marx (later, Basil Rathbone and Madeleine Carroll would replace departing cast members). The concept of the series was to present Hollywood celebrities in a format where they could demonstrate to the listening audience an erudite grasp on important subjects of the day. Circle, despite sponsorship by Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, was expensive to produce (the stars netted $2,000 to $2,500 each weekly) and left the airwaves in July of that same year because according to writer Carroll Carroll in None of Your Business, “It might have worked if actors weren’t all children.” (Carroll dismissed the series as “radio’s most expensive failure.”)

“If I ever do any more radio work, I want to do it on Suspense, where I get a good chance to act,” Cary once remarked about “radio’s outstanding theatre of thrills.” Grant made four appearances on the popular anthology drama, doing the Cornell Woolrich-penned “The Black Curtain” twice on December 2, 1943 and November 30, 1944, and “The Black Path of Fear” (also based on a Woolrich tale) on March 7, 1946. It was Cary’s Suspense swan song that would feature his most well-regarded acting turn on the show—in addition to becoming a radio classic—as he and Cathy Lewis played a couple who happen to give a lift to a female hitchhiker (Jeanette Nolan) suspected of being an escaped mental patient in “On a Country Road.”

Because Cary Grant also spent time on the airwaves joking and joshing with the likes of Al Jolson, Abbott & Costello, Burns & Allen and Eddie Cantor, he was schooled enough in comedy for his second try at a weekly radio series in 1951. Cary frequently appeared on The Screen Director’s Playhouse (one of his best Playhouse showcases has him taking over Joseph Cotten’s bad guy role in a November 9, 1950 broadcast of Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt), and on two occasions—July 1, 1949 and June 9, 1950—he reprised his starring turn from his 1948 box office smash Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House (with Myrna Loy as his co-star). The 1950 Playhouse broadcast featured Cary acting alongside his real-life spouse Betsy Drake, and in November of that year the couple performed in an audition for a series based on the film, Mr. and Mrs. Blandings. Blandings had an impressive pedigree (it was directed and produced by Nat Wolff, who also did The Halls of Ivy) but its scripts were horrible (Drake even tried her hand at writing, as “Matilda Winkle”) and ratings dismal; it ran briefly from January 21 to June 17, 1951.

After the failure of the Blandings series, Cary Grant mostly limited his radio participation to The Lux Radio Theatre, where among the productions were aural adaptations of such Grant classics as The Bishop’s Wife (1947) and People Will Talk (1951). In the meantime, the beloved actor continued to be a favorite with moviegoers; he acted in two more Hitchcock films (including 1959’s North by Northwest; director Hitchcock believed Cary was his definitive movie hero) as well as popular entries like Houseboat (1958), Indiscreet (1958) and Operation Petticoat (1959). By the 1960s, a graying Cary demonstrated he could still wow the ladies with vehicles like Charade (1963) and Father Goose (1964); only when he completed 1966’s Walk Don’t Run (a re-working of the Joel McCrea-Jean Arthur romantic comedy The More the Merrier) did he decide to take his last bow. 1970 was the year when “Archie Leach” would be recognized by his peers “for his unique mastery of the art of screen acting with the respect and affection of his colleagues” with his honorary Oscar, and he continued to be one of Hollywood’s respected statesmen (he received Kennedy Center Honors in 1981) until his death in 1986 at the age of 82.

Radio Spirits’ George Burns & Gracie Allen CD collection Treasury features a pair of broadcasts that guest-star our birthday boy…and personally, I think they’re among the funniest shows that the comedic husband-and-wife ever did. (Longtime Burns & Allen writer Paul Henning once remarked in an interview with historian Jordan R. Young in The Laugh Crafters that Cary loved working with George & Gracie: “When can I be on again? You don’t have to pay me, I’d just like to come on.”) We also invite you to check out a December 7, 1950 broadcast on our Screen Director’s Playhouse set in which Grant and leading lady Irene Dunne are re-teamed for a production of “My Favorite Wife.” In addition, Cary is one of many celebrities featured in the delightful DVD of Paramount Pictures’ classic celebrity newsreel shorts, Hollywood on Parade, Volume 1…and you can listen to Mr. Grant display his playful tuneful side with three song selections in the 2-CD set Did You Know These Stars Also Sang? Hollywood’s Acting Legends. Happy birthday to the incomparable Cary Grant!